by Willie (Bil) Weaver

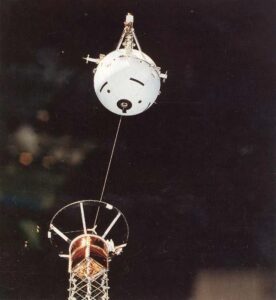

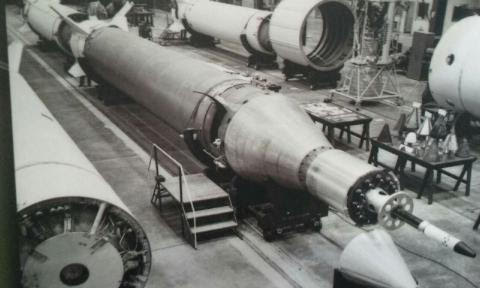

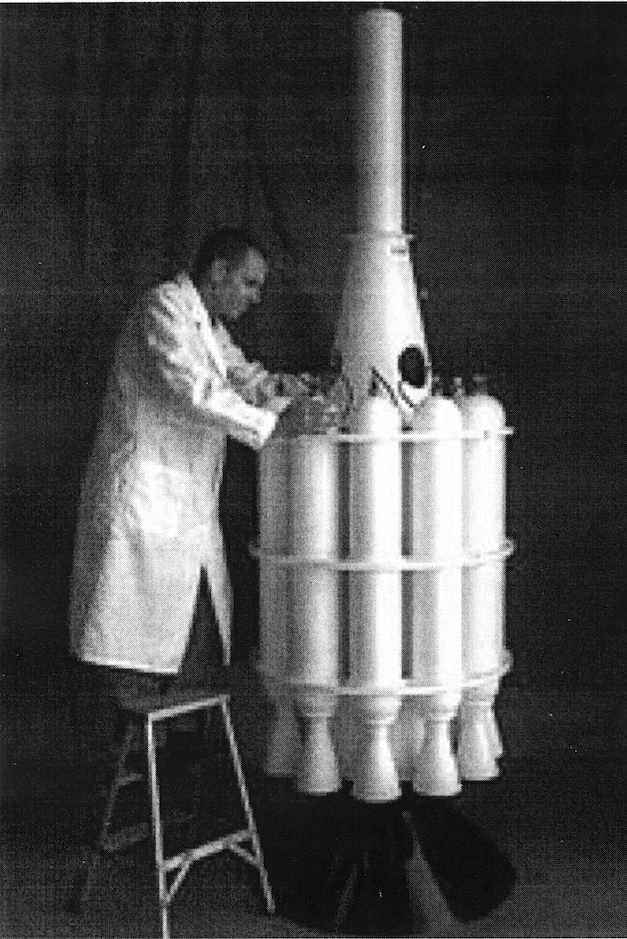

I was a Co-Op Student alternating semesters of work between the University of Alabama and The Army Ballistic Missile (ABMA). I When I arrived at Redstone Arsenal in the spring of 1958, a new series of Redstone Rockets, called Jupiter-C, were being tested. For this new series, the fuel tanks had been lengthened, the instrument compartment made smaller and lighter, and second and third stages had been added to the basic Redstone configuration. The second stage was an outer ring of eleven scaled-down Sergeant rockets; the third stage was a cluster of three scaled down Sergeant rockets grouped within the outer circle formed by the second stage rockets. The second and third stages were contained in a “tub” atop the vehicle.

The official purpose of theJupiter-C class of Redstone rockets was to perfect the ability to carry a warhead above the atmosphere and have it survive the fiery re-entry on its way to the target area. Dummy warheads were coated with special materials designed to melt and carry heat away from the warhead itself. These tests provided the basic research for warhead protection and for the heat shields used later in the Apollo and Shuttle programs.

Tucked away inside the Jupiter-C program was a well-known secret agenda to assemble one of these vehicles with a 4th stage that could place a small object into orbit about the earth. One of the Jupiter-Cs received special handling and security. When we conducted the SFT, which included testing all the electronics necessary to activate the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th stages, the Commanding General and Dr. von Braun were on hand to observe the test.

When that test was completed, the whole assembly was wrapped and carried to a sealed hanger to await the possible permission to orbit a satellite. At the end of a semester of work, I returned to studies a the University of Alabama.

THE JUPITER MISSILE

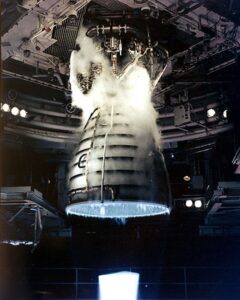

Upon returning to Redstone Arsenal in mid-September 1957, I was again assigned to the Instrumentation Test Group. The Test Organization was still processing Jupiter-C Redstones for warhead re-entry tests and were making preparation for the testing of a new series of missiles called JUPITER. The Jupiter missiles were based on Redstone technology but had larger diameter tanks and ungraded guidance, control and instrumentation systems which gave them an extended range.

THE SPACE AGE BEGINS

On October 4, 1957, I was inside the instrument section of a Jupiter rocket heating temperature sensors with a hand-held hair dryer. This process was to verify the proper installation and operation of the many temperature sensors that were flown on the military rockets.

We used various other methods to check the operation of the other sensors, such as pressure, vibration and position. These tests were required to track the performance of the rockets as they were flown for further testing. I was getting into position to heat another sensor when I heard a commotion outside the rocket and was instructed to come out and listen to an important announcement.

Everyone knew that the Russians had a fledgling missile program and had announced that they planned to participate in the International Geophysical Year (IGY) with a satellite of their own. But it had been assumed by all that the USA would be the first nation to successfully place an artificial satellite into earth orbit. That assumption had just been shattered. The announcement was that the Russians had placed the world’s first artificial satellite into orbit. Now every 90 minutes, as we listened in our telemetry ground station to the beeping Sputnik-I, we were reminded that the USA had lost the Race to Space.

On December 6, 1957, I was seated at the dining table in Ma Miller’s Boarding House situated on West Clinton Avenue, Huntsville, Alabama, on the current site of the von Braun Civic Center. Meal time was usually a rather noisy time with many different conversations among the 20-odd men seated at the large table, but that day everyone’s attention was on the scene being played out on the small black-and-white television set in the corner of the room.

The Navy was making its attempt to launch a VANGUARD rocket with the USA’s IGY satellite. It would not be the first into space but at least the USA could join the Russians in space exploration. The final countdown continued and at “Zero” we saw the smoke and flame and then the liftoff.

Suddenly the screen was filled with the bright flash of a violent explosion and what was left of VANGUARD fell back to the launch pad. Surprisingly, instead of sighs and moans of despair, a spontaneous cheer of elation arose in the room. Most everyone there realized that the Navy’s failure meant that the local missile team might now get a chance to redeem the honor of the USA.

Back in the Spring of 1957 we had finished our tests on a Jupiter-C Redstone Rocket specifically outfitted to deliver a satellite into earth orbit for the “International Geophysical Year Program” (IGY). That rocket and its cargo were then placed into storage because “Washington” had made the decision that the Navy and its VANGUARD missile program would have the privilege of being the first to place a USA satellite into orbit.

After the launch of Sputnik-I and the failure of the Navy’s VANGUARD rocket, Dr. von Braun assured President Eisenhower that our team had the hardware available and could put up a satellite in short order. The Army / von Braun Team was given the go-ahead. The satellite-capable Jupiter-C Redstone was taken out of storage, unwrapped, and we immediately began to get it ready to go to the launch site.

I had worked many long shifts helping to prepare the rocket for an attempt to bring the U.S. space program even with the Russians.. Finally, on January 31, 1958 the the Redstone Rocket launch was successful and the Explorer-1 satellite was in orbit and sending back data.

The U. S. Army’s rocket team had entered the Space Age!

Explorer Satellites

In the summer of 1958 after another semester of study at the University of Alabama, I was again working as a Co-op student at Redstone Arsenal. During this work session I was assigned to work as part of a team manning a telemeter trailer in support of tests on another Explorer satellite which was to be launched soon atop a Jupiter-C rocket.

I remember watching various meters as the data from a vibration test of the satellite was recorded on long rolls of photographic paper encased in canisters. When the tests ended, we took the canisters from the recorders and rushed them to the darkroom for developing.

As we spread the rolls of developed data, still not quite dry from the developing process, on the viewing table, Dr. James van Allen, puffing a cloud of smoke from his pipe, would intently examine the various squiggles to determine how his satellite and its radiation detectors had survived the vibration test. When we had short breaks from our hectic test schedule, Dr. van Allen enjoyed explaining the mechanisms and purpose of his experiments.

He was also very concerned that the radiation belt above the earth might mean that man would never be able to go safely into space. The measurements to be made by instruments on this satellite would map the areas of intense radiation. If it could be determined that the radiation was limited to only certain areas, then there might still be a place in space for man and even for satellites that will make true global communication possible. Two Van Allen Probes were flown and shed light on the type of radiation that man and machine would encounter as further space exploration proceeded.