by Willie (Bill) Weaver

After high school graduation in 1955, my life suddenly became quite busy. I enrolled at the University of Alabama and was taking two mathematics courses on the accelerated summer schedule, I was working 20 hours per week as an office assistant (gofer) for the University Extension Division, and I was helping with the construction of our new home.

In mid-September I began my first regular semester of college study and was signed up for a full load of classes. I soon realized that I needed more time for my course work so I resigned from my job as an office assistant at the end of September. We moved into our new house in Peterson and my Dad found a buyer for the business in Tuscaloosa. He had plans to spend the next year building more rental houses. In preparation for that, he had purchased the right to salvage the lumber and other materials from four houses located on the L & N Railroad property. He planned to employ my skills as an electrician in construction of the new rentals, but he impressed upon me that I was not to allow it to interfere with my studies.

I was very absorbed in my studies but was somewhat aware that deconstruction had started on the first of the salvage houses. One morning in mid-October, as we were about to have breakfast, my Dad told us that he had a stomach ache, so he would go get his work crew started and come back later for breakfast. I went to the campus, went through classes and labs for that day and returned home in the afternoon. No one was home and there was a note on the door telling me to go to my aunt’s country store for a message. I learned that my Dad’s stomach-ache had worsened and he was now in the hospital where surgery for the removal of an intestinal blockage was scheduled for the next day.

The intestinal surgery was successful but the patient almost died. My dad had contracted hepatitis in his early 20s and supposedly made a full recovery. Because they found a tumor on his large intestine, they made a thorough examination of his abdominal cavity and ruled out cancer. However, they discovered that he had cirrhosis of the liver and it was slowly dying. The trauma of the surgery put his body into shock which was impeding his recovery from the surgery.

He spent the next 12 months either in the hospital or bedridden at home. Our family doctor told my mother to disregard the surgeon’s opinion that Dad had less than 6 months to live, and that he would work with us for Dad’s recovery. Needless to say, the plans for building more rental houses were set aside and my Dad sold the salvage rights to the other 3 houses. Mr. Hill, who headed up the work crew, finished up the demolition of the first house and I assisted him in getting the salvage materials into storage.

As the Fall semester was coming to an end, I was having concerns about being able to stay in school. The proceeds from the sale of the Tuscaloosa store and the salvage buildings were being depleted by rising medical expenses. At this point the family income was totally dependent upon the, sometimes erratic, rents from 10 properties. The rents were sufficient to cover normal household expenses but left little room for much else.

While sitting with my Dad during one of his stays in the hospital, I mentioned that I was considering going back to work as an office assistant with the University or maybe take a lighter course load and find a better paying full-time job. He did not like that idea, at all. He had always planned for me to get the college education that he had missed out on. He told me in no uncertain terms that I was not to let a job interfere with my course work. Somehow, he intended to keep me in school.

This would be a good time to say something about the response of our relatives and the community to by Dad’s disability. I cannot count the number of times that people brought us groceries and even prepared meals. There was an uncle who helped my Mother put gas in her car and then paid for it. Another uncle, who ran a television shop in Birmingham, brought in a television set and put up the antenna tower that it took to receive the signals from the Birmingham stations. A cousin took care of some plumbing problems. Renters paid early or decided it was time they caught up on their back rent payments. Various forms of support and prayers were supplied by so many others.

In mid-January of 1956, I finished the Fall semester with good marks and registered for the Spring semester. A payment of some back rent came in with almost the exact amount to pay the university fees and buy books.

THE CO-OP PROGRAM

In February 1956, I was in the 2nd semester of Basic Physics when the Professor announced that he would be cutting his lecture short because we had a guest who would tell us about a special opportunity for Physics students. The guest told us that he was there to recruit Co-Op Students to work at REDSTONE ARSENAL. I had no idea what a “Co-Op Student” was or where “REDSTONE ARSENAL” was.

His next remark was that we would be working with Dr. Wernher von Braun and his team of Rocket Scientists. I did know who Dr. Wernher von Braun was. I immediately became interested in everything he had to say. He explained that “Co-Op” was short for “Cooperative Training Program” where a student would attend school for a semester, then work for a semester, and continue to alternate that schedule until graduation. I soon learned that REDSTONE ARSENAL was located a little over 100 miles away in North Alabama near the city of Huntsville.

As he continued explaining the program and how we could become a part of it, I sat there contemplating what a blessing I was being offered. I had reached a crisis point in my hopes for a college education. While my mother and I had been praying for Dad’s return to health, he was praying for a way to keep me in school. As we looked back on that time we were convinced that God answered all of our prayers. I had been granted a way to continue in college and have some income to share with the family. My father began to regain his strength and was eventually able to start a new business.

THE REDSTONE ROCKET

In June of 1956 I came to REDSTONE ARSENAL to work my first term in the CO-OP Program. I spent several hours in orientation meetings and a few hours of filling out forms for background checks, status of health, and security clearance. During orientation, I attended a ceremony where Dr. Wernher von Braun and an Army officer welcomed us new CO-OPs to the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. As part of that ceremony, we went through a receiving line for a handshake with the Officer and Dr. von Braun. Dr. von Braun took the time for a short conversation with each of us 20 or so CO-OPs. After completing the orientation, I was taken to a large hangar like building to meet my supervisor and workmates. It was there that I got my first glimpse of a REDSTONE ROCKET.

For the next 3 and 1/2 months, I would be a part of the crew which checked out and tested a series of these rockets before and after they were carried to a test stand and fired. The specific task of my unit was the testing of the sensors and gauges scattered throughout the rocket. After the final tests, the rockets would be shipped to either the Florida or the New Mexico test ranges for actual flights.

The Redstone rocket was a direct descendant of the German V-2 rocket which rained down terror on the British during World War II. In the early days the Redstone was often referred to as “The V-3”, but that term was soon forbidden. These rockets were military missiles designed to carry either conventional or nuclear warheads to the enemy. In 1958 one of these rockets was used to explode an atomic war head at the edge of space over the Pacific Ocean, resulting in a period of electronic communication blackout over much of the Pacific area.

In mid-September, 1956, I returned to the campus of the University of Alabama to continue my studies in Physics and Mathematics. At the end of that semester, I headed back to Redstone Arsenal.

When I returned to Redstone Arsenal in the last week of January 1957, I was assigned as an assistant to the Systems Tests Conductor. His responsibility was to plan and coordinate the test program for the rockets. Each of the test disciplines, such as instrumentation, telemetry, pneumatics, hydraulics, and guidance and control, would perform their part of the total test program and then verify their interfaces with the other disciplines. Then a final test, which was called a Simulated Flight Test (SFT) would be conducted. In the SFT all systems were powered and operated in the same mode and sequence as an actual flight but without any fuel in the system. During this time I gained valuable experience in planning and conducting large scale systems tests involving the crews from multiple disciplines and the total rocket systems, but without any fuel in the system. During this time I gained valuable experience in planning and conducting large scale systems tests involving the crews from multiple disciplines and the total rocket systems.

THE JUPITER-C

A new series of Redstone Rockets, called Jupiter-C, were being tested. For this new series, the fuel tanks had been lengthened, the instrument compartment made smaller and lighter, and second and third stages had been added to the basic Redstone configuration. The second stage was an outer ring of eleven scaled-down Sergeant rockets; the third stage was a cluster of three scaled down Sergeant rockets grouped within the outer circle formed by the second stage rockets. The second and third stages were contained in a “tub” atop the vehicle.

The official purpose of the Jupiter-C class of Redstone rockets was to perfect the ability to carry a warhead above the atmosphere and have it survive the fiery re-entry on its way to the target area. Dummy warheads were coated with special materials designed to melt and carry heat away from the warhead itself. These tests provided the basic research for warhead protection and for the heat shields used later in the Apollo and Shuttle programs.

Tucked away inside the Jupiter-C program was a well-known secret agenda to assemble one of these vehicles with a 4th stage that could place a small object into orbit about the earth. One of the Jupiter-Cs received special handling and security. When we conducted the SFT, which included testing all the electronics necessary to activate the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th stages, the Commanding General and Dr. von Braun were on hand to observe the test. When that test was completed, the whole assembly was wrapped and carried to a sealed hanger to await the possible permission to orbit a satellite.

During that Spring Semester work period, I had two other things going on in my life. The University of Alabama had an extension center in Huntsville and I discovered that I could speed-up my progress towards a degree by taking courses there. I had just completed Semester-1 of the required Basic Chemistry on the main campus, so I signed up for Semester-2 in Huntsville. Otherwise, I would have had to wait a full year to catch that 2nd semester on the main campus.

Although I was working 58 hours a week and taking a college course, I still found time to meet and date a special girl. She was working as an engineering aide at one of the fledging aerospace companies that sprung up in Huntsville to support the Army’s rocket development. When I returned to the main campus in June 1957, I corresponded with her and even managed a couple visits back to Huntsville during the summer session.

Back on campus I was taking a full load in an effort to graduate by June 1959. During that semester I begin to profit from having some actual work experience, as I soon became the go-to person for the other students and Lab Instructors when it came to operating and trouble-shooting the laboratory equipment.

THE JUPITER MISSILE

Upon returning to Redstone Arsenal in mid-September 1957, I was again assigned to the Instrumentation Test Group. The Test Organization was still processing Jupiter-C Redstones for warhead re-entry tests and were making preparation for the testing of a new series of missiles called JUPITER. The Jupiter missiles were based on Redstone technology but had larger diameter tanks and ungraded guidance, control and instrumentation systems which gave them an extended range.

THE SPACE AGE BEGINS

On October 4, 1957, I was inside the instrument section of a Jupiter rocket heating temperature sensors with a hand-held hair dryer. This process was to verify the proper installation and operation of the many temperature sensors that were flown on the military rockets. We used various other methods to check the operation of the other sensors, such as pressure, vibration and position. These tests were required to track the performance of the rockets as they were flown for further testing. I was getting into position to heat another sensor when I heard a commotion outside the rocket and was instructed to come out and listen to an important announcement.

Everyone knew that the Russians had a fledgling missile program and had announced that they planned to participate in the International Geophysical Year (IGY) with a satellite of their own. But it had been assumed by all that the USA would be the first nation to successfully place an artificial satellite into earth orbit. That assumption had just been shattered. The announcement was that the Russians had placed the world’s first artificial satellite into orbit. Now every 90 minutes, as we listened in our telemetry ground station to the beeping Sputnik-I, we were reminded that the USA had lost the Race to Space.

On December 6, 1957, I was seated at the dining table in Ma Miller’s Boarding House situated on West Clinton Avenue, Huntsville, Alabama, on the current site of the von Braun Civic Center. Mealtime was usually a rather noisy time with many different conversations among the 20-odd men seated at the large table, but that day everyone’s attention was on the scene being played out on the small black-and-white television set in the corner of the room.

The Navy was making its attempt to launch a VANGUARD rocket with the USA’s IGY satellite. It would not be the first into space but at least the USA could join the Russians in space exploration. The final countdown continued and at “Zero” we saw the smoke and flame and then the liftoff. Suddenly the screen was filled with the bright flash of a violent explosion and what was left of VANGUARD fell back to the launch pad. Surprisingly, instead of sighs and moans of despair, a spontaneous cheer of elation arose in the room. Most everyone there realized that the Navy’s failure meant that the local missile team might now get a chance to redeem the honor of the USA.

Back in the Spring of 1957 we had finished our tests on a Jupiter-C Redstone Rocket specifically outfitted to deliver a satellite into earth orbit for the “International Geophysical Year Program” (IGY). That rocket and its cargo were then placed into storage because “Washington” had made the decision that the Navy and its VANGUARD missile program would have the privilege of being the first to place a USA satellite into orbit.

After the launch of Sputnik-I and the failure of the Navy’s VANGUARD rocket, Dr. von Braun assured President Eisenhower that our team had the hardware available and could put up a satellite in short order. The Army/ von Braun Team was given the go-ahead. The satellite-capable Jupiter-C Redstone was taken out of storage, unwrapped, and we immediately began to get it ready to go to the launch site.

In the meantime, my romantic life was proceeding. Anne and I were married in mid-January and she would move to the campus with me in February to complete my Junior year.

I worked many long shifts helping to prepare the rocket for an attempt to bring the U.S. space program even with the Russians. On January 31, 1958 the launch attempt of the Explorer-1 Satellite was under way at Cape Canaveral, Florida. It was with reluctance and regret that Clark, another coop student, and I turned in our badges at 4:00 pm, checked out of Redstone Arsenal and headed back to Tuscaloosa for the new semester at the University of Alabama. We had spent the day monitoring the launchsite activities and did not want to leave until the launch was successful, but the University’s registration process waited for no one.

As we rode through the hills of North Alabama, what newscasts we could hear make no mention of a rocket launch. We went by to see Clark’s mother in Birmingham. She met us at the door, appearing very excited. She quickly led us to her living room urging us to come see what they were showing on the television. The REDSTONE Rocket launch had been successful and the Explorer-1 satellite was in orbit and sending back data. The U. S. Army’s rocket team had entered the Space Age!

Explorer Satellites

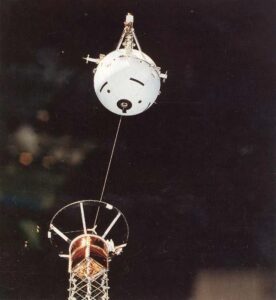

In the summer of 1958 after another semester of study at the University of Alabama, I was again working as a Co-op student at Redstone Arsenal. During this work session I was assigned to work as part of a team manning a telemeter trailer in support of tests on another Explorer satellite which was to be launched soon atop a Jupiter-C rocket. I remember watching various meters as the data from a vibration test of the satellite was recorded on long rolls of photographic paper encased in canisters. When the tests ended, we took the canisters from the recorders and rushed them to the darkroom for developing.

As we spread the rolls of developed data, still not quite dry from the developing process, on the viewing table, Dr. James van Allen, puffing a cloud of smoke from his pipe, would intently examine the various squiggles to determine how his satellite and its radiation detectors had survived the vibration test. When we had short breaks from our hectic test schedule, Dr. van Allen enjoyed explaining the mechanisms and purpose of his experiments.

He was also very concerned that the radiation belt above the earth might mean that man would never be able to go safely into space. The measurements to be made by instruments on this satellite would map the areas of intense radiation. If it could be determined that the radiation was limited to only certain areas, then there might still be a place in space for man and even for satellites that will make true global communication possible. Two Van Allen Probes were flown and shed light on the radiation belts surrounding Earth. This information allowed for the implementing of proper protection from the radiation for man and machine as further space exploration proceeded.

SATURN ROCKET

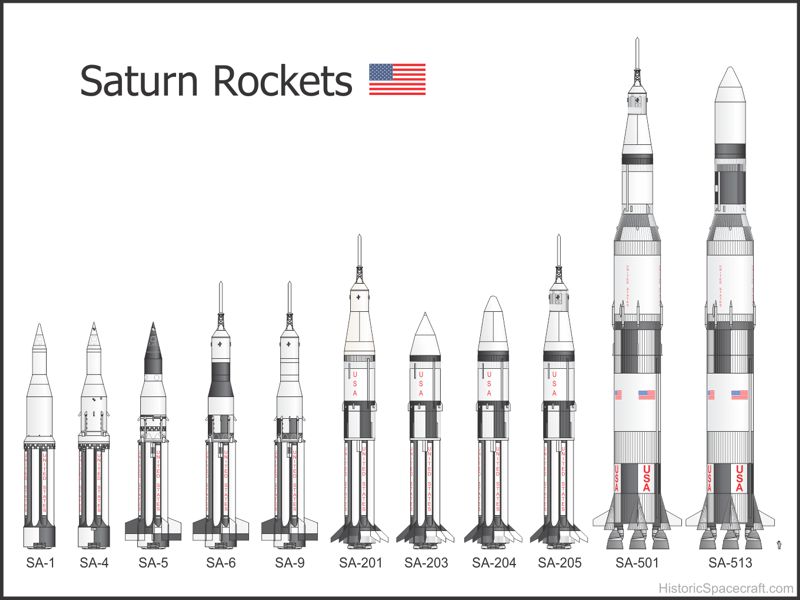

During this period, the main test groups were still processing and testing various versions of the Redstone and Jupiter missiles for both military operations and space exploration. There was also talk of a new and bigger rocket with Code-Name NOVA. NOVA would be built by clustering 8 Redstone tanks around 1 Jupiter tank and adding eight larger engines. Such a vehicle could be used to deliver larger warheads over a longer range or used to put larger satellites into earth orbit.

In mid-September 1958 I returned to the U of A campus, completed 2 more semesters of study and was rewarded a Bachelors of Science Degree in May 1959.

FULL TIME JOB

After graduation I returned to the Army Ballistic Missile Agency as a full-time employee, but the future status of the Army / von Braun team was uncertain. NASA had been established and was given the responsibility for all non-military aspects of space exploration and the Air Force had been given the responsibility for all long-range military rocketry efforts.

The von Braun team were still Army employees but were spending much of their efforts in support of NASA projects. Also. they were still developing short-range military rockets for the Army. When someone pointed out that the term “Nova” meant “Exploding Star”, the new long-range missile, NOVA, was renamed SATURN. If it continued in development, it would be managed by the Air Force or restricted to only “peaceful” purposes. SATURN soon became the primary candidate to send men into long-term orbit and to the moon.

FROM ARMY to NASA

In September 1960 we gathered in the parking lot of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency Headquarters as President Eisenhower conducted a ceremony which transferred the von Braun group and its facilities to the newly created NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. We would no longer work on military rockets, but concentrate our efforts on civilian space vehicles. We were also preparing a REDSTONE rocket to carry the first USA astronaut into space during the next year.

MERCURY-REDSTONE

In May 1961, Alan Shepard, flying on a Mercury-Redstone became the second person and the first American to travel into space. After processing 2 more Mercury-Redstones for sub-orbital flights, we begin to concentrate our full efforts on preparing the much larger launch vehicle known as the SATURN.

PRESIDENTIAL CHALLENGE

In 1963, President Kennedy gave NASA the goal of placing a man on the moon before the end of the decade. The next several years of my career were spent in the development, construction and testing of the SATURN series of rockets that were used to perform various missions in earth orbit and to support the Apollo Program which put 12 men on the Moon.

During the early phase of the Saturn-Apollo program I participated in the testing of the prototype and test units of the Saturn stages. When the production of the man-rated units were turned over to American industry, I worked with the NASA offices that had oversight of the contractors.

SKYLAB

The Moon Missions were getting all the public attention, but the Saturn vehicles were being put to use for other things. As all the elements for the moon missions were put into place, one of the more interesting and productive NASA projects was the SKYLAB Program.

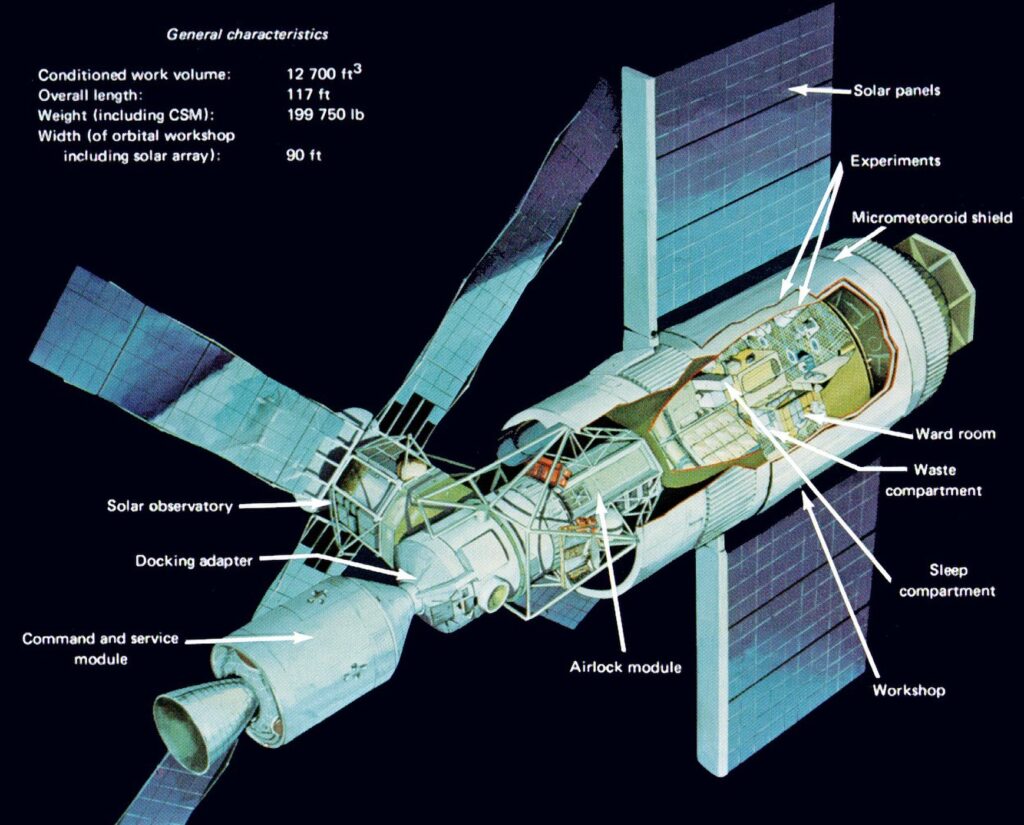

SKYLAB was really the world’s first Space Station. It was placed into orbit about the earth in 1973, right after the Apollo moon missions. It consisted of The Orbital WORKSHOP, The Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM), an Airlock and Docking Adapter, and solar-panels for electrical power. When the crew arrived, the Command and Service Modules completed the SKYLAB Space Station.

The Workshop contained laboratory space and living quarters built inside an unused fuel tank from the SATURN-5 third stage project. The main purpose of the workshop was to study the effects on the human body of extended stays in space, especially the effects of zero gravity. The Workshop was the first place that astronauts in orbit were not confined in a cramped capsule. In the WORKSHOP they were able to move about in normal fashion during their daily activities. Data gathered on the astronauts during 3 extended missions provided valuable information for the design of equipment to accommodate men in future space flights such as the Shuttle and the International Space Station.

The Apollo Telescope Mount contained eight instruments to study the Sun. Its observations of the Sun greatly enhanced our understanding of the Sun. Of major interest for future space flight was the improvement in our ability to predict solar flares and the knowledge to design for protection from the resulting intense radiation.

The Apollo Telescope Mount was designed and built at Marshall Space Center where we received and installed telescopes from several astronomical organizations. I led one of the test groups that prepared the assembly for flight.

The Airlock and Docking Adapter provided the passageway from the Command Module into the Workshop and was the staging area for extra-vehicle activity. In addition, it contained the control panel for the ATM and its instruments.

Photographic and radiometric instruments for studying the Earth were also mounted here. These early studies of the Earth’s surface and atmosphere yielded volumes of data for understanding our home world.

Three 3-man crews worked in SKYLAB. The last crew left on February 12, 1974 and no one ever returned. SKYLAB stayed in orbit until 1979. When it reentered the atmosphere, most of it burned up but some pieces fell in the Indian Ocean and on Australia.

I consider the SKYLAB Missions to be NASA’s greatest Scientific Accomplishment of the 20th Century, while the Moon Missions were the world’s greatest Engineering Accomplishment of the 20th Century.

APOLLO-SOYUZ

By the early 1970’s, both the USA and the Soviet Union were putting men into space on a regular basis and the two countries agreed to develop a means to connect their and our spacecrafts in orbit for potential rescue efforts. On July 15, 1975, an Apollo spacecraft launched carrying a crew of three and docked two days later on July 17, with a Soyuz spacecraft and its crew of two, thus demonstrating the ability for mutual rescues.

After the APOLLO-SOYUZ mission, the USA withdrew from manned spaceflight to put all its efforts and money into the development of the SPACE SHUTTLE. No one expected that it would be 6 long years before we again sent men into space.

THE SPACE SHUTTLE

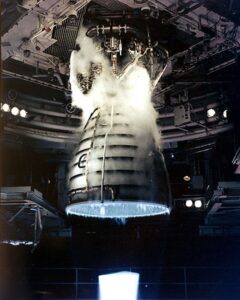

Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas managed the overall Shuttle Program and Marshall Space Flight Center supported it by supplying the engines and solid rocket boosters.

THE SPACELAB

In the spirit of international cooperation, the European Space Agency agreed to supply a laboratory module to fly in the payload bay of the shuttle. This module was named SPACELAB.

It had its genesis in SKYLAB and became the progenitor of the INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION. I transferred to the NASA Program Office that had the responsibility to coordinate the SPACELAB-to-SHUTTLE interfaces. I worked in that position through the development phase of the SHUTTLE and SPACELAB vehicles.

HUNDREDS OF SPACE EXPERIMENTS

In 1988, when the SPACELAB became operational, I moved to a Payload Integration Group and spent the next 14 years of my career aiding those wanting to fly their EXPERIMENTS on the SPACELAB, SHUTTLE, SOYZU, and the INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION.

In this position I got to meet many of the interesting people who developed and conducted experiments in space. These experiments range across just about every scientific and engineering discipline; from human cellular study to the forming of metal in zero-gravity.

Forty-seven years with the Rocket Team and the Space Program. Along the way we raised 3 sons who have provided us with 9 grandchildren and 6 great-grandchildren. We helped organize and establish a new church and enjoyed the many advantages of living in Alabama’s ROCKET city. We also acquired, built, and managed several residential rental properties until disposing of them after retirement.

Today, I volunteer as a Docent at the U. S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Here I meet people from all over the nation and world, and enjoy answering their questions and telling them of my adventures in our country’s space program.