by Roger Chassay, March 18, 2014

This is the 50th year celebration of the July 16th, 1969 launch of Apollo 11 and transport 18 March 2014.

I. UNUSUAL MANAGEMENT SUCCESS

About 1990, I was selected to manage a new NASA project, which involved the development of an entirely new, space qualified glovebox to be used by astronauts on Spacelab flights to conduct potentially hazardous experiments in space. NASA had very limited funds for new experiment payloads at the time, but the European Space Agency (ESA) was very interested in collaboration with NASA on new projects.

Somehow we convinced ESA to provide all the funds needed to develop this important new facility, with me as a NASA employee actually managing and directing their contractor in The Netherlands. To show the proper ‘quid pro quo’, we agreed to provide ESA with a token ‘no cost’ use of one of our Space Shuttle Middeck Lockers on a future Space Shuttle flight—for a small experiment of their choosing.

The Glovebox would be developed and built to our exact NASA needs—with no cost ceiling!! Sure, ESA also provided a project manager to officially oversee the development contract, but he liked and respected me, so he quietly and unofficially gave me free rein to provide day-to-day direction of his contractor. Late in the development process, when ESA ran short of funds for completion of this Glovebox, I negotiated directly with The Netherlands government, specifically their Director of Research, for their government to provide the additional funding needed to complete the Glovebox development and prepare it for launch into space. Their Director also liked and respected me, and let me decide how much funding would be the appropriate contribution by The Netherlands!!

Of course, we coordinated the official paperwork through the appropriate NASA International Affairs Office, but they were busy with other matters at the time, and allowed us a great deal of flexibility as to how we documented this highly unusual “deal”.

In 1992, the brand new Glovebox was successfully flown into earth orbit on Space Shuttle mission USML-1. As a result, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center got wonderful results from 16 microgravity experiments in fluids, protein crystal growth, zeolites, flammability, and bubble behavior. This, in turn, provided the momentum for future use of that Glovebox, and the development of a much larger Glovebox for the International Space Station—sometimes referred to as the “Backbone” of the International Space Station’s vast experiment accomplishments.

II.EARLY SPACE PROGRAM MISTAKE DUE TO USE OF BOTH METRIC AND ENGLISH UNITS

In 1985, I was the NASA project manager for a $50M class payload called the Fluid Experiment Facility (FES). We had had great difficulty in developing this highly complex apparatus for use in the microgravity of earth orbit. However, with numerous ‘patches’ or quick fixes to work around design problems, we had successfully gotten it aboard the 1985 Spacelab 3 flight of the Space Shuttle. The control room assigned to us was very crowded, and very noisy, but we accepted it and worked two shifts per day, 12-18 hours per day for some of us, for the seven day mission.

During one night shift about midway through the mission, I heard one of my team members yell out a question above the din in the room, wanting to know a particular temperature reading. Another team member across the room looked up that parameter, and yelled back the temperature reading. The first team member updated his software table with that temperature input, and also updated the associated stored commands for the FES to execute. During the next communications pass, he uplinked these FES commands to the orbiting Spacelab.

Then I heard another question yelled “Did you give me that temperature in degrees Fahrenheit or Centigrade?” The answer was yelled back “Fahrenheit”. Unfortunately, the uplinked commands had assumed “Centigrade”, so the engineer had to hastily revise the commands and uplink the corrected commands, with only seconds remaining in the communications pass. We almost had a serious error in the experiment processing of the FES!!

I had always been an advocate of the use of the Metric System since my college years, when I learned that it simplified and made more efficient our calculations—with fewer errors. So, I knew at that moment in this noisy control room, this “close call” could have been averted if NASA and the U.S. Congress had fully addressed this issue, and earlier provided the needed funding to abolish the use of the old awkward English system of units within NASA. However, I also knew that for years this lack of action was likely to continue, so I concluded that it would take more than this “Close Call” on FES to rid NASA of this hidden risk.

Space photo of Earth’s Northern Lights

Fast forward to the year 1999, when the NASA Mars Climate Orbiter $250M mission was a total failure—directly due to a mislabeled space data table that was using the English system of units, whereas the ground software was using the Metric System!!Yet, as this ‘story’ was being initially written by me in 2001, NASA and the U.S. Congress had still not yet provided the needed funding to rid NASA of this continuing risk.

III. UNLIKELY COMMENDATION

Around 1965, the Chrysler Corporation’s Space Division (CCSD) at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans was highly challenged during the development of the booster rocket stage (S-1B) of the Saturn IB launch vehicle. This was the launch vehicle to be used to practice manned spacecraft maneuvers in earth orbit in preparation for the Saturn V launch vehicle to later send the Apollo manned spacecraft to the moon for lunar landings. During these challenging days of the S-1B rocket development, each mistake was costly in time, money, and credibility for Chrysler, so their management insisted on virtually mistake free manufacturing of the flight hardware.

One day a large puncture was discovered in the outer metallic skin section of the one of the fuel tanks of the S-1B booster stage that was needed at the Kennedy Space Center very soon for an upcoming launch. The technician who discovered the puncture reported it to his Chrysler management. I was a new NASA employee in the NASA Marshall resident office there, and was sure this terrible incident would cause Chrysler top management to rant and rave, and to severely discipline the workers on the production floor—and someone would be fired.

To my surprise, their President made a profound announcement that the reporting of this damage was an outstanding and exemplary event. His rationale was that their company already had their most experienced, best trained, and highly motivated employees on this very important NASA development, and that it would be foolish to fire one of these top-notch employees who made a mistake, and replace them with a ‘second string’ employee. However, he also announced that any employee hiding such mistakes would be immediately fired.

He insisted that each mistake made would be promptly followed by an intense investigation to determine the specific “root cause” of the mistake, e.g., poor lighting, insufficient training, improper tool availability, employee fatigue, etc. In summary, he put his full trust in his employees, not wanting to blame them for problems, since he knew that something else in the workplace is typically the root cause of virtually all mistakes made by an excellent team of space workers.

IV. ANOTHER UNLIKELY COMMENDATION

During the Saturn rocket development program to launch Apollo spacecraft to the moon, Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) had a program called Manned Flight Awareness (MFA) to alert employees and contractors, as well as their subcontractors and suppliers, that our jobs involved the safety and lives of the astronauts. To test the efficacy of the MFA program, a series of regional workshops were held at various locations around the U.S.—to meet with NASA MSFC contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers of Saturn rocket launch vehicle equipment.

In one such workshop, an executive of an electrical relay supplier was shocked to hear that his parts were life critical for astronauts flying on a rocket launch. He said that his company had earlier received an order to supply 50 electrical relays to the Chrysler Corporation. This relay purchase order didn’t designate any specific use by Chrysler, so his company didn’t know if the relays were to be used in Chrysler air conditioners, automobiles, or military tanks. When he discovered the relays were being used in Chryslers S-1B rocket booster stage for critical astronaut life and mission applications, he recommended we use their highest quality relays, which only cost ~$15 more per relay than the medium quality relays which Chrysler had ordered!

Numerous other similar communications foul-ups were revealed at those regional MFA workshops, indicating that our mailings to the CEOs and organization Presidents were mostly being discarded and not being used by these organizations. It was concluded that we should report to our MSFC Center Director, Dr. Werner von Braun, that our Manned Flight Awareness program was basically a failure. The briefing to Dr. von Braun was made using viewgraphs, with about a dozen MSFC employees attending the presentation. I was the lowest ranking employee there, available only to answer questions that might come up, so I remained silent throughout the presentation. I was certain Dr. von Braun would be very angry at our lack of success with the MFA program.

When all the viewgraphs had been shown, he calmly stated that he was pleased that we had held the workshops, and now that we had identified the problem, he was highly confident that we would resolve it. He then walked to the conference room door, opened it, and shook hands with each of us as we departed the room!

V. PERSONAL DIFFICULTIES WORKING IN A LARGE ORGANIZATION

STORY A:

Knowing that ‘time was of the essence’, since an available NASA river barge was scheduled to leave MSFC on the Tennessee River within 24 hours of my concoction of this plan, I made a few phone calls early one morning to the MSFC manufacturing area. I told two supervisors there that I immediately needed a couple of large lifting cranes as wells as crane operators, and some technicians to accomplish the movement of the old rocket stage, and a large truck with a driver for transportation of the shipping cradle down to the MSFC dock on the Tennessee River. These supervisors had never heard of me, but even though I was a junior employee, I apparently sounded authoritative on the phone. So they immediately recruited about 30 people to accomplish this somewhat complicated task.

When I arrived at the manufacturing buildings area about 30 minutes later, I expected them to challenge me a bit, asking what my authority was. Or at least for me to provide some paperwork transferring the ownership of the cradle, and probably ask me for charge numbers for their employees’ time reporting, as well as for the needed packing supplies. Instead of presenting me with some bureaucratic problems, they were pleased I was there to oversee and supervise the entire operation—although I was personally a little reticent to be directly involved at first, seeing the ‘huge’ team of people and the giant cranes moving into position.

The workmen were apparently glad to do some outdoor work, and enthusiastically, yet carefully accomplished the many subtasks involved in the effort. My precious shipping cradle made it to the river barge with about two hours to spare, and I had saved NASA $100,000, with inflation equivalent to a savings of well over a million dollars as this is written.

Feeling elated that I, as a junior employee, had accomplished such a large, important task in only four hours—with NO paperwork—I headed to my office to resume my normal duties. As soon as I arrived, our secretary told me my GS-16 executive boss needed to see me right away. I entered his office and was “chewed out” for not submitting an input for weekly report that morning, submitted routinely to our top MSFC management . He admonished me, saying that I knew this was a mandatory weekly task for each of his employees. I explained that my almost ‘heroic’ task of getting the shipping cradle onto the river barge took precedence over my preparation of a routine status report of earlier activities. He disagreed, again admonishing me. He never acknowledged my ‘heroism’ for the time-critical task that saved three months of schedule and also the avoidance of $100,000 cost!

STORY B:

As a new supervisor at the Marshall Space Flight Center in 1975, I thought there was no project too difficult for me and my team to tackle. Therefore, we signed up to developing three scientific payloads per year for launch into suborbital missions from the White Sands Missile Range. I named the project Space Processing Applications Rocket, or SPAR. Each payload required my civil service and contractor team to develop from scratch between four and ten complex experiment apparatuses, to conduct materials experiments in 4-5 minutes of near weightlessness.

Almost miraculously, we were able to do this extremely well for the first three suborbital missions, although I wore holes in the soles of two new pairs of shoes in the first six months of this project, having to walk among several buildings each day to coordinate the far-flung actions of our dispersed ‘matrix’ team. However, on the fourth mission disaster struck. BIG TIME!! None of the four experiment apparatuses worked properly, and we got absolutely no scientific results.

Our primary advocate and source of funding at NASA Headquarters was an extremely bright PhD and an experienced executive. He was very understanding of this mission failure, knowing he had obtained a “bargain” for the first three near space missions, costing him only a one to two million each to obtain important new scientific data. He requested that I visit his office in Washington DC to explain what had happened to this fourth mission.

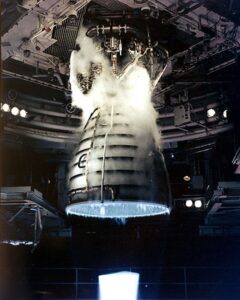

I prepared the briefing charts and provided a pre-briefing to our top MSFC management. Unfortunately for me, the MSFC Center Director had zero tolerance for flight failures, as he and his team were wrestling daily with the difficulties of developing large manned rockets for the Space Shuttle, which couldn’t be permitted to fail during launch, due to the possible risk to the lives of the astronauts. At that time they were dealing with resolving several catastrophic Space Shuttle rocket engine failures during ground testing, although the MSFC team and their successors had never experienced a flight failure in the previous 18 years of their numerous space rocket launchings.

So when I walked into the briefing and told the Director and his large senior staff of the four experiment failures during a single mission, the room got really quiet. The Center Director told me to rework my briefing charts to show that all the MSFC flight equipment worked well, but that the contractor-provided experiment apparatuses failed to work. These were experiment apparatuses from four prestigious space organizations, the Jet Propulsion Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, General Electric Aerospace, and Grumman Aircraft Corporation.

The following week I again briefed the MSFC top management, using the revised approach the Center Director had instructed me to use for my briefing charts. This time the Director reversed course and was very disturbed that it appeared that I was not taking responsibility for MSFC’s management responsibility of flight preparations in a manner that would have ensured mission success. He harshly directed me to rework my charts again.

The next week, I faced the same tough audience for the third time, saying my sponsor at NASA Headquarters was not upset by the experiment failures, but was becoming impatient that I had not arrived in Washington DC to explain the details. I then presented the twice-reworked charts, which attempted to preserve the perfect MSFC space record, yet acknowledge we could have done more to determine the flight-worthiness of the contactors’ experiment apparatuses prior to the flight. The Director this time “shot the messenger”: ME. I was angrily told that the charts were unfit to be presented to NASA Headquarters.

Following that meeting, two senior MSFC staff members volunteered to work with me to further rework the charts. These reworked charts were then presented the next week by my supervisor, who had worked directly with the Director in previous assignments. I attended that fourth briefing, but was silent throughout. Again, the Director was furious at the message portrayed by the charts, and deemed the charts to be unacceptable.

I returned to my office and sat there in the dark for about two hours, planning my possible resignation from NASA. I envisioned me preparing a typewritten note to be placed by me that night under the door of the Personnel Office’s Director. Eventually, with the moonlight shining through my office window, I decided not to resign, but to ‘tough it out’.

Within a few days I summoned enough courage to confidentially get travel orders, take my unapproved charts and travel to visit my sponsor in Washington D.C., providing my “UNOFFICIAL” version of the failure causes. He was dumbfounded that I, as Project Manager, could not give him an official presentation, although he was pleased to finally hear the real story. With the subsequent resumption of six more successful SPAR launches, the SPAR IV problem wasn’t discussed again at MSFC top management meetings.

To my surprise, MSFC continued to assign me to exciting, challenging, and very fulfilling work assignments, although my future promotion possibilities evaporated one by one over the subsequent 10 years that that MSFC Director remained in office.