by Gary Hitt

Spacelab was developed by the European Space Agency (ESA), coordinating the efforts ten participating European governments. It was a modular laboratory designed to fly in the cargo bay of NASA’s Space Shuttle. It could accommodate a wide variety of experiments and could be reconfigured as necessary for each mission.

In 1983, IBM decided to terminate its Spacelab contract and leave Huntsville; a Request For Proposal was issued to find a replacement. TRW, the company I worked for, submitted a bid, and we won the competition. TRW’s job would be to maintain all the generic Spacelab software and to deliver mission-specific software for all future Spacelab missions. I had worked on our proposal, and when TRW won the competition, I joined the project.

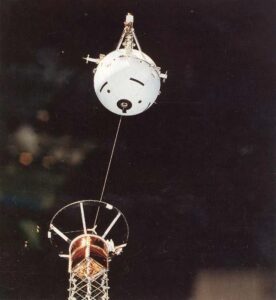

Instrument Pointing System

There was a subsystem of Spacelab called the Instrument Pointing System (IPS), a very complex and critical piece of equipment. It was being developed by Dornier Systems at a facility in southern Germany. I had written the IPS section of our proposal, so I was asked to lead TRW’s IPS-related activities. We assembled a team of TRW engineers to relocate to Germany and work with the Dornier engineers before IPS delivery.

We were very concerned about the IPS software. There was a lot of it, it was very complicated, and (in our opinion) not well documented. IPS development was behind schedule and over budget, and I suspected that Dornier was anxious to deliver this system to NASA and cut their losses. We knew that once the software was delivered, we would be responsible for it.

I was concerned that TRW and Dornier might have an adversarial relationship, with them anxious to get this system out the door and us reluctant to accept responsibility for something that was not quite finished. But I maintained a good relationship with Fred Urban, the Dornier IPS software manager, and Renato Renai, an Italian engineer representing ESA at Dornier.

I accompanied NASA engineers and managers on 8 trips to the Dornier facility in southern Germany and spent a total of 13 weeks there in meetings and reviews prior to software delivery to MSFC.

Often, at the end one of my trips to Dornier, Urban would give me a mag tape with the latest version of IPS software to take back to MSFC, along with a letter that described what was on the tape and authorizing me to have it, helping me get it through security checks in German and US airports.

After IPS software delivery to MSFC, Dornier engineers—there were two as I recall—spent time at MSFC working with TRW engineers preparing for first use of the IPS on Mission SL-2. They could not get through the gates to the Arsenal without an escort with a security clearance, so every morning I would meet them in the parking lot at the Martin Road entrance, get them signed in, and escort them to work.

Since the IPS was designed to operate in a zero-g environment, it could not be fully tested pre-flight on the ground. The first full test would be on-orbit.

The IPS was used on three Spacelab missions: for solar studies on Spacelab mission SL-2 and for astronomical studies on the Astro-1 and Astro-2 missions. For several tense days at the beginning of each of the SL-2 and Astro-1 missions, the flight crew and ground support personnel worked around the clock trying to get the IPS working. Principal Investigators who had instruments mounted on the IPS were seeing hours, then days, pass without getting any data. Finally, with procedural changes and on-orbit software changes, the IPS worked. Had it not worked, it would have been a heart-breaking disappointment for scientists with instruments on the IPS who had spent years in preparation for these missions.

Launch of Spacelab Mission D-1

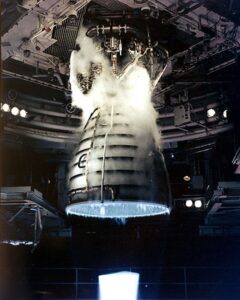

I was at the Kennedy Space Center for the launch of the Spacelab D-1 mission, the first of two missions that we did for DFVLR, the German space agency. The word “awesome” is much overused these days, often for things that aren’t really awesome at all. But a Shuttle launch was truly awesome. Watching all that power unleashed, the blazing engines, billowing smoke and steam, the sound wave hitting and washing over me brought tears to my eyes. It was a very emotional experience.

The D-1 mission was carried to orbit by the Shuttle Challenger on October 30, 1985. It was the last flight of Challenger before it exploded during launch in January 1986. I was in the NASA cafeteria watching the launch on TV when it happened. I and all those watching were stunned. What went wrong? How could this have happened? Could the crew have survived this? Still trying to process all this, I went to our project manager’s office and sat down. He was working at his desk. He looked up and said, “Well, how did the launch go?” I told him what had happened, and we spent the rest of the day watching TV accounts of the accident, speculation about causes, and the possibility of crew survival.

We didn’t launch another Spacelab mission until the Astro-1 mission in December 1990, almost 5 years later. We lost a lot of good people from the project during the long interim period between missions, but managed to keep a strong core team together.

I was on TRW’s Spacelab project for 11 years, during which time we delivered software for 12 missions. I had moved from working as an engineer to engineering management. I was Deputy Project Manager when I retired in 1994.

I made many friends and have fond memories of the NASA projects that I worked on. In my aerospace career, I worked on projects for NASA and for the Department of Defense—several Army projects, an Air Force project, even briefly for a Navy project. But the NASA projects—Apollo, Viking, Spacelab—are the ones I enjoyed the most and the ones I am most proud to have been a part of. With them, I always got to see the results of my work. Things that I had worked on actually flew in space, unlike my DoD projects, some of which I hoped that what I had worked on would never be used.

My wife and I retired in Huntsville, so I often see some of my NASA and TRW friends. Those of us still around are getting a bit long in the tooth, but we still get together every now and then. Those who worked on Spacelab meet for lunch a couple of times a year to relive old memories and stay in touch with old friends.

I recall the night in Fort Worth in 1960 that I saw the Echo 1 satellite. As I watched it arc across the sky, I thought how satisfying it must be for someone who worked on it to realize that he had a part, however small it might have been, in creating this amazing thing. I remember thinking that I wanted to be part of something like that, some remarkable human achievement that I could look at and know that I had been a part of it, even if only a small part. Looking back at my career—Apollo, Viking, Spacelab—I feel like I did that. I think the Apollo Program, landing humans on the moon and bringing them safely back, is the most significant achievement of our generation. I am so fortunate and grateful to have had a small part in it.

It would make a good story to say that, inspired by seeing Echo 1, I resolved to pursue an aerospace career. But that’s not how it happened. My aerospace career came about because of fortunate timing. When I got out of the Army in 1966 and began my civilian career, the Apollo Program needed people with my background. When the Apollo Program began shutting down in the 70s, Viking started up. Then there was Spacelab until I retired in 1994. My career coincided with the golden age of space exploration.