Background Information

You can add or edit information about this individual by clicking

“Click here to suggest an edit or add more information to this entry” at the bottom of this page.

Employee Info

- UniqueID

- N05726

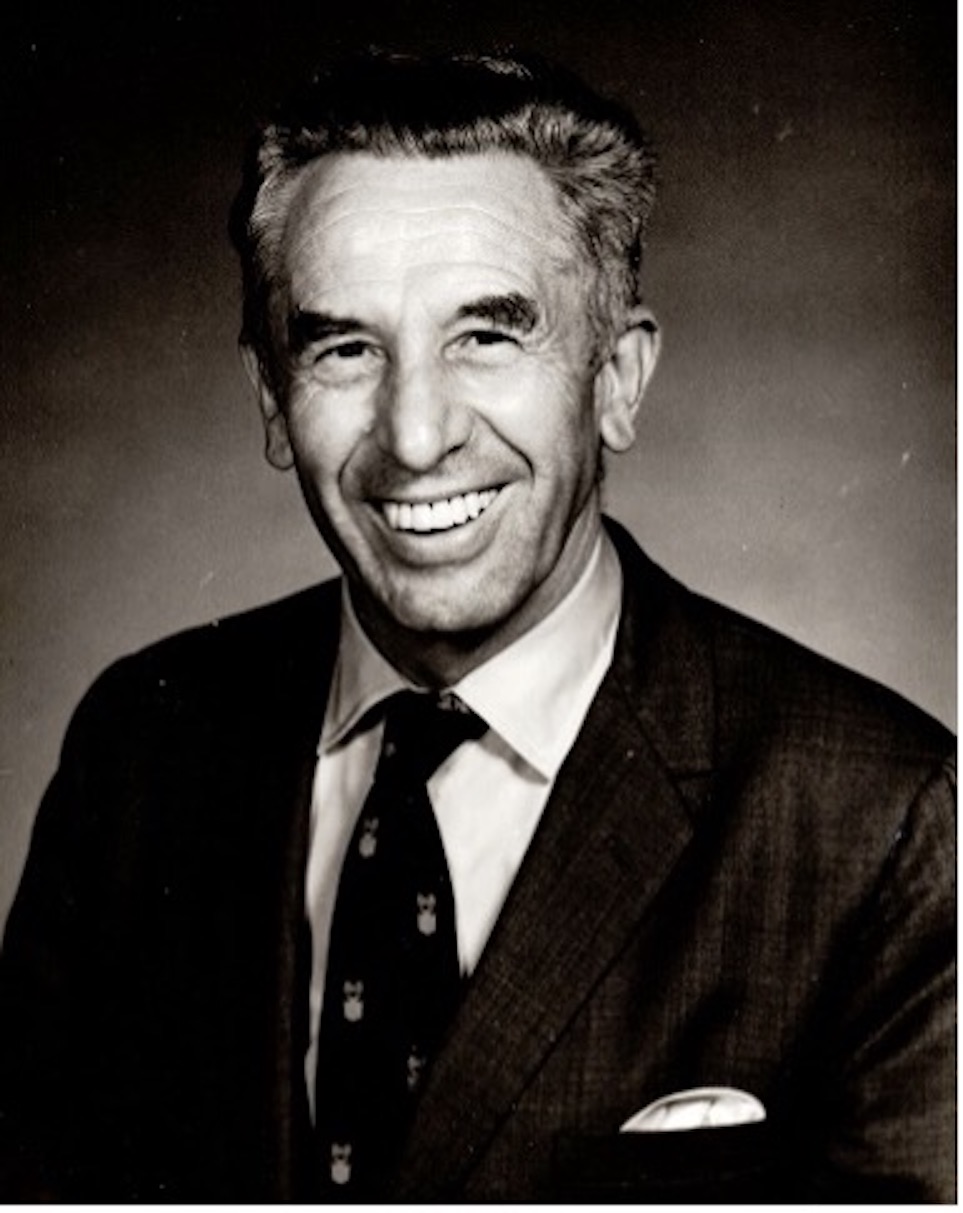

- Photo

- First Name

- Gerhard

- Middle (1)

- B

- Middle (2)

- Last Name

- Heller

- Suffix

- Biography

- The history of Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), one of NASA’s largest field centers, is more familiarly associated with the fire, smoke, and roar of the Apollo rockets of the 1960s; but it also had another notable element. The smallest of its initial Research and Development laboratories served as an incubator and major contributor to the foundation of space science in the 20th century. Not all of the research ideas and laboratory studies initiated by laboratory leaders came to fruition immediately; some of them eventually played a part in MSFC’s contributions to NASA’s extraordinary Great Observatories achievements that extended into the 21st century. In September 1969, following the successful Apollo 11 moon mission, a NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal was awarded to Gerhard B. Heller. This was an especially fitting recognition for someone who played a significant role in establishing that early space science foundation. The award citation signed by the NASA Administrator rightfully honors his leadership role in mentoring and directing others. However, Gerhard was also a space pioneer as an individual contributor, particularly with regard to electric propulsion and arc engine research. In the 1950s emergence of rocket and missile technology for space exploration purposes kindled interest in combining thermal and chemical physics to produce plasma arc energy. The need to understand and simulate spacecraft travel and reentry conditions resulted in funding research for the military services and NASA. Gerhard was involved extensively in this research while working for the Army and later for NASA. His arc engine concept, developed at Plasmadyne Corporation under the auspices of MSFC, was flight tested in September 1961. Between the mid-1950s and 1963, he was the author or coauthor of many publications and papers on electric propulsion and the plasma jet (for example, “Propulsion for Space Vehicles by the Thermodynamic Process," presented at the Ninth Tripartite AXP Conference, Quebec, Canada, May 1959; and "The Plasma Jet as an Electric Propulsion System for Space Applications," presented at the American Rocket Society Meeting, Washington, D.C., November 1959). Gerhard Bernhard Heller earned his undergraduate physical chemistry degree at the Institute of Technology in Darmstadt, Germany, in 1938 and his M.S. degree in 1940. He was a member of the initial Wernher von Braun team of rocket scientists and engineers that relocated to Fort Bliss, Texas, in 1945 to work for the U.S. Army. He was also among the members of the German-American team that once again relocated, this time to Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, in 1950 to work for the U.S. Army. Beginning in 1951, the first year of the University of Alabama Redstone Arsenal Institute of Graduate Studies, Gerhard also served as a lecturer in thermodynamics. His next relocation was with the now greatly expanded team that transferred from the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) in 1960 to form the core of the newly established NASA MSFC. He began at MSFC in the Research Projects Office (soon to become Space Sciences Laboratory, or SSL) as the Deputy Director of the organization and also chief of the Space Thermophysics Branch (eventually Thermodynamics Division). He continued in these dual roles until becoming the Director of SSL by early 1969. Tragically, during the high point of his career Gerhard was fatally injured in an automobile accident in early autumn 1972, cutting short a distinguished 27-year career of space research and exploration during the beginning decades of the U.S. space program. In its summer issue of 1973, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics journal “Astronautics and Aeronautics,” [p. 76, p. 80] published a memorial tribute to him authored by Ernst Stuhlinger. Dr. Stuhlinger had worked with Gerhard for more than three decades and knew him as both a genuine person and a respected professional colleague, and his memoriam captured the essence of Gerhard Heller, the space explorer employee and leader. “Gerhard was born in Eschwege, Germany, in 1914. He came to the United States in 1945 as an associate of Wernher von Braun. For 16 years, from 1956 to 1972, he was associated with the same laboratory, first known as the Research Projects Laboratory of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and later as the Space Sciences Laboratory of the NASA George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, both in Huntsville, Alabama. He directed this laboratory from 1968 to the time of his death. “The history of Gerhard Heller’s life reflects a deep love for nature which permeated his professional work as thoroughly as his private life. This love of nature embraced the world of atoms as well as the world of stars and galaxies, and very specifically it embraced his fellow men, his friends, and his family. How happy was Gerhard in the middle of a group of friends, or colleagues, or his young coworkers, chatting and joking and debating. He was always a driving force in the conversation, a generator of new ideas, a spark for activity, and a source of unlimited enthusiasm, whether the subject concerned a study in his laboratory, or the analysis of a new theory, or piloting a small airplane, or climbing a mountain, or skiing in Aspen, or acquiring a new telescope for his associates, or skin diving off Catalina Island, or beginning a joint research project with a university. He was most encouraging to his young colleagues when they presented new plans for their work, but he was relentless in his demand for careful and sound work. His criticism for shallow thinking could be as outspoken as his praise for a worthy accomplishment. He spent countless hours with his co-workers, discussing the results of their research studies and the proper course of action for further progress. The list of proud young doctors of science who earned their degrees in his laboratory is ample proof of his fruitful work with young scientists. “Gerhard Heller’s own studies in physics and chemistry began at the Institute of Technology in Darmstadt, Germany, in 1932. After a short period as assistant professor in the Department of Physical Chemistry, he joined the Rocket Development Center under Wernher von Braun in Peenemuende, Germany, in 1940. He soon became the thermodynamics specialist in the Department of Rocket Motor Development, and he made decisive contributions to the liquid-rocket engines which powered the Peenemuende rockets, most notably the V-2, which was to become the first mass-produced large liquid-propellant rocket in the world. “In 1945, a small group of the Peenemuende staff came to the United States to continue work in rocketry. The group was stationed in Fort Bliss at the outskirts of El Paso, Texas, until 1950, when it moved to the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. At Fort Bliss, Gerhard’s work concerned at first a thermodynamic analysis of the ramjet, a propulsion system for high-flying supersonic aircraft. When the development of the Redstone missile began, Gerhard concentrated his efforts again on liquid-rocket engines; but his work program soon expanded to incorporate thermophysics of bodies that re-enter the atmosphere from great altitudes, the physics and engineering of liquid-hydrogen systems, and the development of electric-rocket propulsion. “Gerhard was one of the pillars in the small group of enthusiasts who, in the early Fifties, began to study possibilities of building and launching a satellite. His task was to conduct a thorough thermal analysis of the solar heating of a satellite under varying orbital conditions and the design of passive systems to control the internal temperature within acceptable limits. He soon became a specialist in this thermal-control work, and he and his co-workers provided the thermal analysis and design for a number of satellites and spacecraft which followed the small Explorer-1 satellite of 1958. Gerhard was extremely painstaking in this work. One day, after the temperature measurements on an orbiting satellite had been radioed back to Earth, he looked over a table full of numbers and graphs with a worried expression. “Do you see this? The satellite skin was almost two and one-half degrees warmer at this point than we had calculated. We must have made an error somewhere.” “As a strong believer in spaceflight and space exploration, Gerhard Heller had been a long-time member of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. In 1963, he proposed that a Technical Committee on Thermophysics should be added to the Institute’s TC organization. His proposal was accepted; and he became a charter member of the committee, and chaired it for two consecutive terms. “During the years after Explorer 1, Gerhard’s work gradually extended over almost every area of space exploration. When manned flight to the Moon began to appear realistic toward the end of the Fifties, he and his associates were among the early students of lunar physics. He began to plan traverses with Rover-type vehicles, and he proposed experiments to measure the thermal properties of the lunar surface. The Sun, likewise, attracted his lively interest; he initiated the development of instruments in his laboratory to make precision measurements of the solar constant from an Earth orbit, and to simulate for test purposes the Sun’s radiations to which a spacecraft will be exposed. Project Skylab enjoyed his and his laboratory’s wholehearted support in many areas, among them thermal design and control, development of radiation-sensing instruments, meteoroid protection, radiation protection, and development of a solar X-ray telescope for one of the principal scientific experiments. His research program included a ground-based study of solar microwave emissions; together with the Naval Research Laboratory, he and his associates engaged in the development of a solar magnetograph of unprecedented spatial and time resolution. Microwave and magnetographic observations are now [were then] part of a worldwide observational program to monitor the Sun when Skylab with its solar telescopes will be [became] operational. Gerhard helped organize this program for NASA in 1971. “In 1968, Gerhard became director of the MSFC’s Space Sciences Laboratory, after having served as deputy director for a number of years. He strongly believed that the Space Sciences Laboratory should be a place of active research in a variety of fields related to spaceflight. Astronomy became his special love. At the time of his death, his laboratory owned four telescopes in Huntsville for observations in the visual and the infrared regions, and it shared ownership of a 1.5-m telescope on Mt. Lemmon, Arizona, with the University of Arizona in Tucson, and the Goddard Space Flight Center. He was a founding member of a local astronomy club, the Rocket City Astronomical Association, and he maintained close contact with a number of the leading astronomers in the country. “The work program of Heller’s laboratory, however, reveals that his interest was far broader than astronomy. In his effort to support spaceflight where he saw an opportunity, he encouraged or initiated laboratory studies in such diverse fields as plasma physics, superconductivity, holography, meteoroid simulation, gravity-gradient measurements, contamination studies, relativity experiments, cosmic-ray observations, gamma-ray studies, X-ray physics, thermophysical investigations, and radiation-shielding studies. In all these projects, he conscientiously developed and maintained a genuine research capability within his laboratory, but he was anxious to have research groups at universities, observatories, and industrial firms join forces with his associates. This effort to augment his laboratory’s in-house capabilities by associations with other research groups gave him a potential for productive work far beyond the capacity of his own laboratory, which never exceeded a total work force of about 130 persons. “Gerhard Heller’s life and work spanned an unusually great arc, and he loved every bit of it. Whatever he did – and he was always doing something – he enjoyed it thoroughly. He was happy to be alive, and he radiated his joy of life to everyone whose path crossed his. With this radiance of joy he will live on in the memories of his colleagues, his friends, and his family.” Ernst Stuhlinger NASA Marshall SFC 1973

- Starting Year

- 1960

- Last Year Served

- 1972

- Honors

- Projects Worked

- Employer

- NASA

- Initial Source

- Lundquist

- Panel #

- III

- Line #

- 54

- Click here to suggest an edit or add more information to this entry.

The entry will be temporarily removed from the search results until MRA has verified the edits.