by Charles Richard Chappell

1 The Uncertain Beginning

It had been a full day. Graduation was less than a week away, and there were many things to complete, not the least of which were the final exams, my last exams at Sidney Lanier High School. I turned into the gravel driveway of my home on the Huntingdon College campus in Montgomery, Alabama. There was a lot on my mind as I parked the 1949 black Dodge at the back of the house. It had been my dad’s “fishing car,” but I was happy to have it as my own after I turned 16.

Entering my house, I was greeted by the sweet smiling face of my mom in the kitchen cooking dinner. My dad called from the den and asked me to come in and watch the evening news; he said that President Kennedy had made a speech to Congress that day proposing a new challenge for America. Sitting down, I heard the president say “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

This was a defining moment and personal challenge for me, the possibility of responding to the president’s grand challenge for America and working to become a space explorer. This opportunity was the culmination of a childhood that had been characterized by both wrenching failure and initial successes that had been part of the journey to find what might make me special in life—the critical self-esteem on which young people and adults alike build their lives. This mysterious inner journey had brought me to this moment.

Both of my parents were professors at Huntingdon, and both were excellent teachers. Winn and Gordon had met as students at Vanderbilt University during the Depression, and I was excited about going there as a freshman that upcoming fall of 1961. My sister, Wendy, and I lived in a home that was a place where education and learning were valued, encouraged, and honored. That environment had been a foundational element of my search for self-worth, especially after my difficult and embarrassing failure at sports.

The America of the 1950s, as it is today, was captivated by sports of all sorts, and young people were continually reminded of the fame and fortune that can accompany their success on the athletic field and the entertainment stage. For me, Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox was the hero. Baseball achievement became my goal, and once I got my first glove in the fourth grade, I began to play wherever I could to prepare for the Little League tryouts.

In the fifth grade, at 11 years old, I joined the tryouts for Little League. I was an acceptable baseball player but not yet an exceptional one. To my great happiness, I was selected to be a member of a new team sponsored by WAPX radio, and as the first game approached, the new team members were given their uniforms and their caps. This was a very big thing for all, and the ability to wear your baseball cap to school and brand yourself as a successful baseball player was of great significance.

The day before the first game, my coach came to my house on the edge of the campus in the afternoon. He sat with me and my parents in our small living room and said calmly that even though the tryouts had been completed, another young man had come along later, and he was an excellent player. The coach told our shocked group that he had decided to put the other player on the team, and since there were only a limited number of spaces, he would need to take me off and would need to get my uniform and cap back.

The success and self-esteem that I had felt in sports became an amplifier of the failure that I felt at that moment. It would be a long time before I would understand the depth and significance of that event in my life. My one initial takeaway was that my life would not be built around a professional baseball career, which I knew Americans valued so highly, but would, by necessity, have to be built around something else. I would have to find some other talent or ability to serve as the foundation of my self-worth in life. This complication seemed difficult to overcome, and what might happen was not at all clear.

It would be another president, Dwight Eisenhower, who would initially open the door for me to begin to find that other ability. When the Russians surprisingly launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, President Eisenhower responded with a clear declaration to the American people that the country had been beaten and that Americans must respond with a focus on science and engineering that would allow them to compete with the Russians. At 14 years old in the ninth grade at Cloverdale Junior High School, I had found some success in my studies of science and math, and now my country was saying to me that these subjects were important in addition to baseball and football. This success became an encouragement to me to continue my newly found journey toward self-esteem.

Empowered by America’s push for science and technology, I increased my study of math and science. This study continued through my 3 years at Lanier, where I was very successful academically, although not at sports, and I began to be recognized by my fellow students as having some special ability. I was even successful in being elected president of my senior class, a position of fellow student attention that was very new to me.

With President Kennedy’s 25 May 1961 commitment of the United States to space exploration, my path was established, and my journey to the adventure of space exploration was confirmed. Young people listen to what their country, through the media, tells them is important, and a nation’s leaders must always be careful and thoughtful to encourage, feature, and support the things that they want their young people to decide to do. Ultimately, the total number of talented people who changed their lives and brought their abilities to the Apollo Moon program was in excess of 400,000.

2 Leaving Home to Follow the Journey of Exploration

The summer heat of Montgomery gave way to the crisp, clear fall temperatures and beautiful colors of Nashville. It was my first extensive stay away from home, and after emptying the bags from the overstuffed car and goodbye hugs, my parents drove away, leaving me with new friends to make and new things to learn in the stimulating and demanding Vanderbilt environment. The university years were meaningful and memorable, and the new colleagues, knowledge, and challenges combined to create a wonderful experience.

In science and mathematics, I began to develop the fundamental tools to become a space explorer. Things were happening in America: Alan Shepard had flown into space in April, and John Glenn was just about to become the first American to orbit Earth. I found the academic environment compelling and interesting and began to learn about the mix of academia and social interactions. Learning to talk about complex science to friends who were not in science was an important talent that would serve me well in the future steps on my space journey. My self-esteem in physics and math continued to grow.

One cool November morning in my junior year, leaving an advanced calculus class in Old Science Hall amid the falling leaves, I noticed groups of students standing together talking and listening to the radio. Seeing a friend in one of the groups, I went over and found shockingly that President Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. The American leader who had inspired so many in the country and who had started me on my personal exploration journey had been taken away. America had lost its leader and inspiration, but the things that President Kennedy had begun for the nation would continue to successful conclusions. Six years after his death, Americans would walk on the Moon, and my dream would continue.

I did well academically at Vanderbilt and, following graduation, worked for the summer in Huntsville, Alabama, for IBM, learning to write computer programs that simulated instruments on the Saturn V Moon rocket that was being built there. Then on a hot and humid day at the end of the summer of 1965 I drove west to Houston to pursue graduate studies at Rice University. Houston was just up the road from Clear Lake, Texas, the new home of the Manned Spacecraft Center, later to become the Johnson Space Center, where the Gemini flights were taking place in preparation for the Moon mission.

At Rice the studies would become more focused on the space adventure as I joined the newly established Space Science Department and began my work with a brilliant Australian professor, Brian J. O’Brien, who was a most successful innovator and achiever in the early days of spaceflight. He had worked for James Van Allen at the University of Iowa prior to joining the new department at Rice. The classroom work was exciting, and it was combined with the opportunity to work in the laboratory developing instruments that would fly on rockets and satellites!

My graduate work at Rice focused on understanding the processes that create the aurora borealis or northern lights. Using data from rocket flights through the aurora and combining them with computer predictions, I was able to understand more clearly how the electrons and protons that rain down on the top of Earth’s atmosphere from space cause the dancing curtains of auroral light. In doing this, I gained new knowledge about this space phenomenon and, for the first time, tasted the thrill of exploration and discovery.

3 Becoming a Space Explorer

While finishing my thesis, I spent a summer working at the Lockheed Palo Alto research laboratory with Dr. Martin Walt, a friend of Dr. O’Brien. The computer programs that Lockheed had developed were ideal to help explain the rocket data. This position set the stage for my first real paying job in space exploration following the completion of my PhD. I was hired as a research scientist at Lockheed in Palo Alto, California, another step on the space exploration journey. In those days many American boys had a dream of driving a Corvette and going to California. After finishing graduate school, saving my money, and getting married, I bought a new Corvette. My new bride, Barbra, and I then drove across America, reliving the television show of the early 1960s. We entered California through the magnificent Yosemite National Park, barely surviving the icy roads of a late spring snow storm in Tioga Pass, and I reported to work at Lockheed in June of 1968. This was a time when the newly developed National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Saturn rockets were beginning to carry astronauts toward the Moon. Just over a year later on the evening of 20 July 1969, we sat holding our young son, Christopher, and watched Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin step on the Moon!

The Lockheed research laboratory had many talented space explorers working in a variety of disciplines. The lifestyle was easy in Palo Alto, and I could ride my bike to work along a public pathway. After lunch each day my colleagues and I would walk on the shady streets in the research area around Lockheed, which was part of nearby Stanford University, and share our stories of the science research experience. Feeling the significance of this collaboration for the science combined with the interpersonal connection to fellow explorers was intensely rewarding.

Exploration and life are full of surprise and serendipity. At work, the funding for my research on the aurora ended, and my boss, Dick Johnson, asked me if I would like to work on a different type of data that were being measured by a satellite instrument that another group at Lockheed had built. I accepted and began to analyze measurements of the very low energy ions, electrically charged particles, which are found in Earth’s upper atmosphere, called the ionosphere, as well as at much higher altitudes in the plasmasphere. These particles, it was thought, were very different from the more energetic particles that caused the aurora (Chappell, 1972)

I would not know until later that this unplanned change to study the low-energy particles would be the exploration challenge and quest that would occupy the remainder of my research career. I would find that these low-energy particles play an important role in creating the more energetic particles that fill Earth’s magnetic envelope, the magnetosphere, and help create the aurora! This area of study revealed significant new things about Earth’s space environment and allowed me to experience the true thrill of exploration in which curiosity, motivation, and determination lead to the discovery of new knowledge and a new sense of self-esteem for the explorer himself.

Then one day after 6 years in California, NASA called from Alabama to see if I would consider coming home. The reason would be to work on identifying space science experiments that could be carried out on human spaceflight missions on the new space shuttle. To follow up the Apollo program and the Skylab space station, NASA was building Spacelab, which could transform a shuttle into an orbital laboratory, with scientists going along to do their research. It was an exciting opportunity to become a NASA scientist/explorer, and I could not turn it down.

In February 1974, I once again drove the Corvette across America and began work at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. This historic rocket-building center had been started by the U.S. Army through the work of Dr. Wernher von Braun and his colleagues from Germany following the end of World War II. The center has an incredible history of rocketry and spaceflight, beginning with the launches of America’s first satellite, first astronaut, first Saturn V rocket to the Moon, and the space shuttle. I had an extra feeling of belonging in Huntsville, where the cradle of space exploration in America was combined with the slower-paced and soft-spoken lifestyle of the South.

Joining that accomplished group of space explorers was a most special honor for me, and I immediately set about planning for space shuttle Spacelab missions of the future and starting my own research group studying the low-energy plasma of Earth’s magnetosphere. The challenges of my life had broadened with the journey toward space exploration, now involving both my search to understand Earth’s space environment and planning human spaceflight missions. Our research group grew, and the talent and teamwork of the group amplified the success and new knowledge through their exciting interchange of ideas.

Our group analyzed data from previous satellite missions and began to propose new instruments for future missions. Three were selected, built, and flown, and I experienced the role of becoming a NASA principal investigator and organization leader. During this same time period, I worked with special NASA mentors, Jack Waite and Bob Pace, to plan a future shuttle/Spacelab mission.

Redstone Arsenal is a sprawling, mostly open area on the west side of the town of Huntsville, at the foot of the Appalachian mountain chain. Bordered by the Tennessee River on the south, it contained laboratory and office buildings and large test stands for rocket engine testing. My space research group grew to include studying the Sun, a source of energy and particles for Earth’s space environment and the upper atmosphere, where the solar and magnetospheric effects could be seen.

One of the leading solar scientists, who came from Boulder, Colorado, to work with us, was Ernie Hildner, a very talented scientist and leader. Ernie was tall and athletic and dedicated to personal fitness. He ran daily to stay fit and asked me if I would like to join him. Because of my childhood sports failure, I had been away from anything athletic in my life for 25 years, focusing on the intellectual and not the physical things. I hesitated to enter that realm of life again, but Ernie encouraged me to come along on a run and slowed his speed substantially so that I could keep up.

Running at lunchtime around the historical open natural beauty of the Arsenal became a regular daily occurrence, and other scientists from the group joined in. The initial days of running were challenging and slow, but gradually, my body began to adjust to the routine, and the distances increased. After about 6 months, Ernie suggested that I should consider participating in the Cotton Row Run, a 10-km race held each spring in Huntsville. This seemed out of the question to me but with Ernie’s training help, I did respectably in the Cotton Row Run. Later, I trained and ran five marathons, including New York and Boston. This experience was a most significant one. Psychologically, it allowed me to see that I did have athletic ability, and it brought the appreciation of physical fitness into my life, where it would stay.

This time period in the 1980s was to be a point of insight into life’s journey for me. My quest to become a space explorer had taken shape, and my journey in life once again included exercise and fitness. Data from my first satellite instrument had shown something that was never expected when it was proposed: a large outflow of particles upward from Earth’s ionosphere into its magnetosphere, challenging the long-held idea that the Sun was the sole supplier of the energetic particles (Chappell, 2015; Chappell et al., 1987; Chappel et al., 2008; Chappel et al., 2017). It was clear evidence of the process of science in which explorers often find things that they are not looking for and these newly found things can be much more important than what was being sought originally. After all, Christopher Columbus discovered the American continents on his trip to reach China and Japan, and Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin accidentally in his laboratory. Serendipity often happens in exploration, and people and nations must choose to explore if they are ever to find the new treasures of discovery.

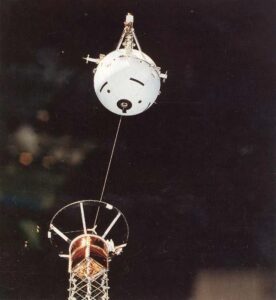

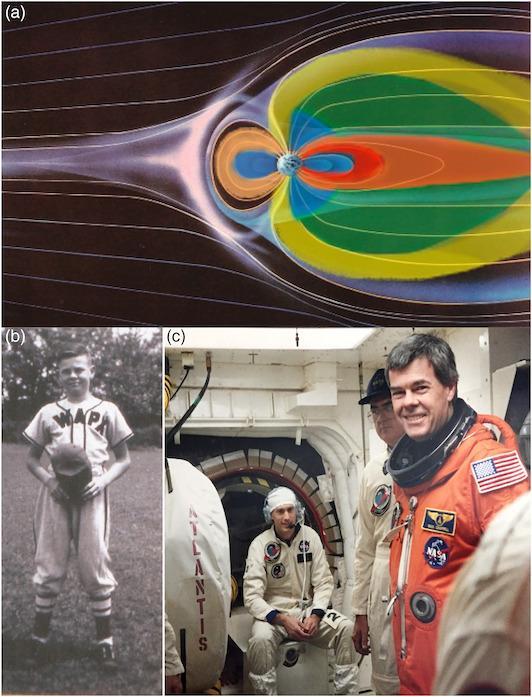

Figure 1

(a) A sketch of the Earth’s magnetosphere as it is shaped by the solar wind flow and filled with up-flowing particles from the Earth’s ionosphere. (b and c) Pictures of two uniforms in my life at ages 11 and 48.

A second element of my space exploration had become the focus on human spaceflight for future shuttle science missions. Planning for the first Spacelab mission began at Marshall in partnership with the European Space Agency. I was appointed as the NASA mission scientist to coordinate the science activities. Together with the European Space Agency project scientist, I led the working group of scientists who had been chosen to fly experiments on the first mission. Scientists from around the world came to Marshall, and the large meetings were held in the center conference room on the ninth floor of the main building, the same room in which Dr. von Braun had held the defining meetings of the Apollo program. With its very large mahogany conference table and paneled walls, the room was a reminder of the many talented space explorers who had come together to create the technology to get Americans to the Moon.

The Spacelab 1 mission was a new approach for human spaceflight in which the scientists on the ground would be able to interact directly with the flight crew members and would also be able to select two scientists who would fly as payload specialist science passengers on the space shuttle. The Spacelab 1 mission flew in 1983 and featured a crew of seven, which included the first two payload specialists who had been selected by the investigators. The very successful mission lasted 10 days, featured more than 70 different experiments and led to a series of more than 20 shuttle/Spacelab missions.

After Spacelab 1 was over, there was a desire to fly a second mission as a follow-up. The investigators on the first mission were asked to choose the two payload specialists and two backups to train for the follow-on mission, which became known as Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science (ATLAS) 1. Because of my involvement in all of the activities in Spacelab 1, I was selected as an alternate payload specialist for the ATLAS 1 mission and began training to fly in space along with the other payload specialists. This selection began another significant chapter in my journey to become a space explorer.

The 7 years of training were an incomparable adventure, working with the other crew members, training in laboratories around the world, and spending more than a year at the astronaut office training at the Johnson Space Center. Charlie Bolden, the ATLAS/STS 45 commander, wanted me to do all of the same training that the primary crew did. This included the terminal countdown demonstration test, a dress rehearsal for the flight that took place at the Kennedy Space Center 1 month before the launch. At this point, the shuttle Atlantis was already on the launch pad with the ATLAS investigations in the payload bay. The crew stayed in the astronaut crew quarters about 15 km from the launch pad.

On the morning of the test, the crew got up, had breakfast in the crew quarters, and then suited up for the ride to the launch pad, where they got onto the shuttle, which was being readied for launch. The crew wore their launch entry pressure suits, added the gloves and helmet, and climbed aboard the space shuttle, where they were strapped into the seats (see Figure 1b and 1c). The practice countdown to launch was started and then aborted so the crew could practice getting themselves out of Atlantis and escaping across the launch pad at the 60-m level to get into the large baskets that could carry them down the slide wire to get away from the launch pad to a nearby bunker for protection.

4 Point of Insight: The Figure in the Carpet

After all of the training was completed, the ATLAS mission lifted off on 24 March 1992. I watched while the shuttle Atlantis carried my friends into space. I then flew on the NASA plane to the payload operations control center in Huntsville, Alabama, where I was the communicator to the science crew members during the flight.

This experience of spaceflight training followed by the all-encompassing involvement in the mission itself caused an emotional change in me. I had attained a role in space exploration at a level that I could never have anticipated when I began my journey as a failed athlete. As the process continued, my feelings and perspectives changed. The emotional movement toward space expanded my view, broadening the perspective from local to spaceship Earth, where the flyer sees no borders anymore, just continents and oceans that display Earth not as a collection of warring nations but as a beautiful spaceship, the Blue Marble.

I went back to the Kennedy Space Center when my crewmates returned and watched as Atlantis touched down at the shuttle landing strip. That journey was at the end, but it was a time of comprehending the full adventure of space exploration—exploring, discovering, and learning. I came to realize that explorers have the great privilege of living an adventure in which they get to feel the personal self-esteem that comes from learning and doing new things and that the explorers themselves have left something new for posterity that was not known when they started their journey as a child. For the explorer, the resolution of the initial challenges in life’s journey is to be able to give back to the world in appreciation of the adventure that the explorer has been given.

4.1 Living in the “What Might Be”

Explorers are curious, motivated, determined people who follow a journey to new discoveries, knowledge, and understanding. Another element of their exploration journey is critical. Explorers need to be optimists. One cannot know the unknown without dedication and work in the face of difficulty. The discovery process involves looking for answers and staying with the work despite the hurdles and failures caused by unsuspected problems. I have always felt that there is a way to overcome a bump in the road and keep moving forward. This feeling was amplified as I worked with other explorers who had the same approach to life.

To me, studying how the Sun-Earth space environment works was like putting together a 20,000-piece puzzle without any picture to go by! Each piece was found from the studies and experiments of all of the explorers in that field of work, and the pieces fit together through the interaction and teamwork of the scientists, engineers, and computer specialists who worked to understand the newly explored space environment.

The optimism of exploration, the ability to face the unknown with the conviction that an answer can be found, is a requirement for a successful explorer. This ability creates a very important by-product for the explorer’s personal life in a broader sense, the pervasive thought in the individual that there are new things that can be done to bring solutions and increased quality of life for all people, the “what might be.” For me, this began with a desire to use my ability to explain science and exploration to the public that had first shown itself when I was a student at Vanderbilt. At NASA, I began to give talks to the public in a multitude of forums, ranging from civic clubs to high-tech companies and to school programs involving students of all ages. These talks were driven by my desire for as many people as possible to learn about the thrill of space exploration and its benefits for the country, especially for America’s young people, who would be making their own personal decisions about their future life goals and journey.

In the early spring of 1994, the Marshall Space Flight Center director, Jack Lee, came by my office to ask if I would consider working in Washington for Vice President Al Gore as the special assistant to the NASA administrator, Dan Goldin. He said that Vice President Gore was visiting Huntsville later that week and wanted to talk with me about helping to lead the creation of the Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) program, a K–12 education program that Mr. Gore had written about in his book Earth in the Balance. The program would involve students around the world in exploring and measuring the environment around them. Later that week, I sat down with the vice president, who asked me to join with another scientist manager, Tom Pyke, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to manage the GLOBE program.

I was excited about this opportunity and a few weeks later found myself sitting in front of the very large picture of the whole Earth taken by the Apollo astronauts on their way to the moon that hung on the wall of Vice President Gore’s West Wing office in the White House. Tom Pyke and I had been asked to come by to talk with the vice president about the progress of our plans to make the GLOBE program a reality. Mr. Gore had announced the program to the world on Earth Day 1994, the week before, and wanted Tom and me to bring together the team of people to make it a reality by Earth Day of the following year.

It was a beautiful time of year in Washington, and the cherry blossoms were in bloom around the Tidal Basin by the Jefferson Memorial, where I had begun to do my early morning runs. Mr. Gore had made arrangements for the GLOBE team to be housed in one of the townhouses across the street from the White House on Jackson Square. He was intently interested in bringing this innovative program to fruition by working with the GLOBE team. With Vice President Gore’s commitment, multiple agencies such as NASA, the National Science Foundation, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Environmental Protection Agency came together to support the program.

I was continuously impressed by the vice president’s dedication to the well-being of our planet and his intellect, organizational skills, and personal sensitivity, empathy, and humanity. His ideas, insight, and commitment had a tremendous positive impact on our nation’s future in very many critical areas. Mr. Gore announced the launch of the program to the world on Earth Day 1995, and more than 20 years later GLOBE is very active and involves students and teachers from more than 100 countries around the world.

I returned home to NASA and in the fall of that year, when the leaves were again turning gold in north Alabama and middle Tennessee, I received a call from Taylor Wang, a friend and payload specialist on one of the shuttle Spacelab flights. Taylor had become a professor at Vanderbilt and asked me if I would talk to his class about future space exploration. I accepted and traveled up to Nashville, where I once again felt the nostalgia and happiness of being on that beautiful campus.

After the class, Taylor and I went by to talk with Chancellor Joe Wyatt. Chancellor Wyatt talked about the need to improve the communication of science and technology through the media to the public and said that he wanted Vanderbilt to be involved in doing that. He asked if I would come back to Vanderbilt and lead a study and activity to improve science communication. I agreed and began to work at the First Amendment Center with Jim Hartz, a former NBC reporter on the space program and host of NBC’s Today Show. This all came together in the beginning of 1996, and for 2 years Jim and I worked to understand how to strengthen the ties to and information flow about science through the media to the public. The resulting book, Worlds Apart: How the Distance Between Science and the Media Threatens America’s Future, was published in 1998 (Hartz & Chappell, 1998).

One of the key products was the creation of a new interdisciplinary major at Vanderbilt, the communication of science and technology, which has continued and has produced graduates who understand science and engineering and who can communicate it to the public. Students were challenged to understand the process of how exploration is actually done and about the nature of the explorers who do it, as well as the challenges of how to tell these fascinating stories of science through the media to the public.

During that magical period of teaching and research at Vanderbilt, I was joined by my new wife, Brenda, who created a wonderful home environment for us and supported my exploration and giving back journey. Following 15 years on the campus at Vanderbilt, Brenda and I returned to live in Huntsville. The move back was very meaningful to me because it brought me back into contact with the many friends and colleagues whom I had worked with at NASA who had been the early heroes of space exploration. Being with these rocket men and women is equivalent to being with the sailors who had crossed the Atlantic Ocean with Columbus. It is they who built the amazing machines that accomplished President Kennedy’s grand challenge and led to America’s success in leaving our home planet and, for the first time in human history, landing on another heavenly body.

I have felt the joy of exploring the space environment of our Earth and how it is continuously changed by our Sun. Being part of this exploration has brought inspiration, satisfaction, and pride to my life. As explorers, our commitment to the what might be of exploration, once ignited in youth, does not diminish. It is the same feeling that caused Columbus to return to the Americas three more times after his initial voyage or that today causes climate scientists around the world to build new satellite instruments and develop predictive computer codes. This new exploration is increasing the understanding needed by humankind to adjust our ways of living compatibly to protect our fragile planetary spaceship. It is also what makes today’s rocket men and women continue to build the machines of space exploration like the Space Launch System, a rocket larger than the Saturn V, which will be the foundation for human travel to Mars, hopefully within the next decade.

Exploration is part of the human psyche and spirit in individuals with curiosity and determination. If one nation becomes misguided and drops back from exploration, as has happened many times in the past generations, other nations will move forward, and to them will go the new science and technology knowledge along with the economic benefits and world leadership that follow.

The what might be of exploration drives the what might be of life as the optimistic, motivated, determined curiosity about our possible future empowers all who want to understand why and use that knowledge for the betterment of life on Earth. To be part of that experience drives the millions of scientists and engineers who live on this planet. It is the same drive that captured a young boy struggling to find his role in life and made it possible for him to live the wonderful exploration journey of adventure and contribution.