By Frank E. Swalley

From Dairy Farm Boy to Rocket Scientist

Fascinating People I Met Along the Way

A Murderer, Football Players, Apollo Astronauts and Others

MASHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER

One of my first assignments was to develop a computer program to predict the propellant boil off of a rocket tank in orbit. While space is cold, the sun’s radiation hitting the tank heats it up even if the propellants are cryogenic. This task also made a good thesis for the completion of my Masters Degree in Aerospace Engineering from Virginia Tech.

At Marshall they didn’t have classes during working hours and so I took a few courses toward my doctorate at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, better known as UAH. However, the race to the moon was on and there wasn’t time for academics nor did advanced degrees seem to help a lot in getting promoted. Being away at school could actually be a deterrent to advancement then.

The next job was to figure out how to feed liquid oxygen and kerosene to five rocket engines on the Saturn 1B from one large tank in the center and eight smaller tanks strapped around it .If one tank became depleted more than the others, then the rocket would be out of balance and be difficult to control. The reason for so many tanks was that the heavy lift Saturn 1B was designed by not starting from scratch but by utilizing existing parts. The small propellant tanks were from the Redstone rocket and the large tank was from the Juno rocket. You also had to account for the possibility of one engine failing and still have even depletion. A fellow engineer, Gordon Platt, showed me how to set up the equations. We interconnected the propellant feed lines and put flow constrictions in the right places. To verify the calculations a scale model was made out of plexiglass and tests run.

BRIEFING APOLLO ASTRONAUTS

Prior to each Apollo mission, I was on a team of two or three people, who briefed the crews on the operation of the Saturn V moon rocket. I covered the structural, propulsion, vehicle lift capability, and mechanical systems. Fred Hammers covered the avionics (electrical systems). We had three sessions with each crew starting about one year prior to their launch and had a final briefing right before launch to cover any changes. Then after each flight, we sat in on the debriefing. The launch vehicle did not take much time in the debriefing, since there were usually very few anomalies, and the launch was such a short time of the total mission.

The astronauts were always after Fred about how they could override the automatic flight control system and fly the Saturn V, particularly in case of emergency. What you would expect from a bunch of military pilots. That capability was limited. The one time that there was an emergency during ascent, the vehicle was hit by lightning. Thanks to the conservative design of the vehicle’s Instrument Unit (I.U.), it survived the strike and did not lose inertial reference (knowledge of where it was in space and time). That good old conservative, German design philosophy (Marshall Space Flight Center). The Houston designed part of the vehicle, the Command and Service Modules lost it all and was updated from the I. U. The astronauts did not take over control of the vehicle during ascent, but said it was quite an experience.

The first time I briefed a crew, I was very nervous. I was in my late twenties and had hardly ever been more than a hundred or so miles from home. We used overhead transparencies that were projected on to a silver screen. I was showing a schematic of the propulsion feed system for the first stage when one of the astronauts asked how the fuel was fed in case an engine went out. I took a permanent color marker and was about to draw on the screen when they stopped me. They all had a good laugh and teased me about it for a long time.

My first briefing was engineering oriented. The crew very nicely told me that was not what they needed and to help me they told several stories. In the early days of the Mercury program one of them was lying on his back in the capsule waiting launch when he heard a loud “bang ” like a shot gun being fired. He said he also jumped out of the seat. As soon as he could speak, he asked the ground crew ” What the hell was that? ” It took them a few seconds to figure out that it was the sound of a pneumatically, actuated valve closing. That valve was located behind his head in the launch vehicle. Another time in the Gemini program the two-man crew was lying on their backs peacefully waiting launch, when, all of a sudden, the vehicle started swaying from side to side and pooping and cracking. They momentarily considered firing the escape rocket to lift them free of the launch vehicle, which they supposed was breaking up underneath them. However, such an action had a high probability of internal injuries on landing impact. Again, they called out to the ground crew ” What the hell is going on? ” Nothing, we are just gimballing the rocket engines to make sure they move during ascent for steering the vehicle. So, the crews impressed on me that they primarily wanted to know what they were going to experience in their five senses- hear, feel, touch, see or smell.

One thing that they could definitely feel was the acceleration to 5g’s during first stage burn, followed by a rapid deceleration to around 1g, when we abruptly shut down four of the five F-1 engines at the end of that burn. They were warned to be ready for the deceleration. All went well until at one post flight debriefing, one of the crew members told me privately that he had gotten uncomfortable during one of the prelaunch delays and had loosened his restraining harnesses and forgot to retighten it prior to launch. When the four engines shut down he found himself flying forward and just managed to throw his hands up in time to stop his face from smashing into the instrument panel located a few inches in front of his face.

Another close call was when the astronauts were on the final leg of the journey back to earth and were trying to store a bag full of urine. It snagged on a sharp corner and spilled the contents into the confined space of the Command Module. In zero g liquids form perfect spheres and float. When a sphere contacts a surface, it spreads out coating the surface completely. There was concern that the acidic urine might short circuit electrical connections. Luckily it didn’t. However, it did coat all the surfaces in the module including the astronauts. It was a smelly crew that returned to earth.

During the Apollo program every time the wives were talking to an astronaut in orbit, they would always remind them to drink their water. One day I asked one of the astronauts why they did that. He said that the water generated in orbit as a byproduct of fuel cell operation tasted like Clorox and they had a hard time making themselves drink it.

THE APOLLO SATURN MISSION NUMBER 203

One of my assignments was to design a system to assure that the propellant in the fourth stage could be fed to the J-2 engine when it was restarted in earth orbit to send the stack on the way to the moon. When we shut the fourth stage down after it had propelled the remaining stack of vehicles into low earth orbit; everything was in zero- g. The remaining half tank or so of propellants would float about as perfect spheres. Since the propellants were cryogenic and were slowly boiling away, we could not confine them in a bladder and just push them out as we did the Service Module hypergols. You had to feed all liquid. You could not feed a mixture of gas and liquid without risking instability in the engine and a subsequent explosion. There was no way on earth to conduct experiments except for a few seconds in a one inch or less diameter container. Also, you could not use cryogenics and get the affects of the boiloff. (You still can’t do such testing today, forty years later.)

McDonnell Douglas was the prime contractor on the fourth stage. Their approach was to let the propellants float until just prior to restart, then fire up some small hyper-golic engines on the outside of the stage generating about 1/10 of a g, which they felt would settle the propellants in the main tanks in time for restart. During earth orbital coast they wanted to design a device like the ones used to separate milk and cream. The device spins the mixture and the heavier substances go to the outside. In our situation the liquid would be slung to the outside of the cylindrical container and the boil off gas could be safely vented out the center. Gordon Platt and I wanted to take a different approach and never lose control of the propellants in the first place. According to our calculations we could propulsively vent the boil off gases along each side of the vehicle generating 1/00th of a g. That acceleration would be enough to maintain control and, also, avoid the extra weight of the McDonnell Douglas proposed system. I presented our ideas to Dr Von Braun and he liked our approach. But, in order to prove it would work, we had to fly a full-sized vehicle- Try our approach first and have the other approach as a backup. We planned out the flight experiment and put together a sales pitch. It was decided that I would go to Washington with Dr. Von Braun to the next Apollo Management Council and make the presentation.

The meeting room was small and only upper management was allowed to sit in on the entire meeting. The rest of the presenters waited outside until our turn came. My presentation was scheduled for later in the afternoon. Dr. Von Braun knew this, and he asked me if I had ever seen Washington before. I told him I had not. He said why don’t you go look around and come back in time for your presentation. I told him I was concerned that if they got ahead of schedule that I wouldn’t be there. He smiled and told me that if that happened he would suggest that go to the next agenda item and pick me up later. I toured Washington, but I came back every hour to see where they were on the agenda. As it turned out everything took longer than expected. The experiment was approved. I thought at the time that I had sold it. However, Dr, Von Braun’s insistence on the necessity of the flight really sold it. All I could have done had I messed up was to have made his job harder.

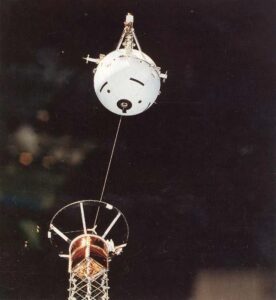

When we returned, they made Gordon Platt the mission manager much to my chagrin. However, I had just read Dale Carnegie’s book ” How to Win Friends and Influence People “. In it was a chapter entitled if you get lemons- make lemonade. I did. As a consolation prize, I was given the job of heading up the flight team sent to Bermuda, which was just under the insertion into orbit point. We had two TV cameras mounted in the top tank manhole cover and a grid painted on the inside wall of the tank so I could judge what was going on and send signals to correct any problems immediately. Since we were not trained flight controllers, we had to go to Houston for six weeks of training prior to the mission.

The timing was trying from a personal viewpoint. I was to report to Houston six weeks before the end of our school year. There was no way I wanted to go there by myself, so we decided Mike would finish the third grade in Houston. His teacher there believed that the Alabama school system was backward and inferior, so Mike had an uphill battle. We worked extra with him after school. She was surprised by his math and science abilities, but he was behind in writing and English. I never will forget her final words to us ” He was too smart to fail “. The two children of one of the families from California did fail. However, there were other problems in that family. The mother was only concerned with her figure and was not too bright herself.

It rained almost the whole six weeks. If all the sunshine hours were pieced together, they might add up to one day. It was an unusually wet spring even for Houston. With the rain came a lot of mosquitoes. When I got home in the evenings, two-year-old Rachel always wanted to hold my hand and walk around the apartment complex, especially the swimming pool. The mosquitoes ate her up and her little legs had big swollen areas where they bit her. Then there were stories about encephalitis in the newspapers caused by mosquito bits. Mike also had trouble with his allergies, and I took the covers off the air vents in the apartment and scrubbed them with Clorox in an effort to get rid of any mold in the ductwork. The new Houston astrodome allowed them to play baseball despite the weather and Mike and I enjoyed a few games. He was also fascinated by the gunslinger, “quick draw” contests in the mall. The time to clear leather was measured electronically.

Not only was I trained as a flight controller, but God also had some training in mind for me. On the first Sunday in Sunday School the teacher announced that he was not going to use the lessons on witnessing in the quarterly. Instead, he was going to teach not theory, but a practical little booklet on ” How to Win Souls”. I still use the methods to this day and the “Soul Winner’s Pocket Guide ” has been republished and is in my briefcase.

When it came time to deploy to Bermuda, we borrowed money from the Redstone Federal Credit Union so Joanne could go too. It was the chance of a lifetime. The Meeks grandparents kept the kids. Initially, there were some long hours briefing the NASA tracking station people and getting ready for the mission. They had only recorded data in the past and were not used to having active mission controllers. And we were not welcomed with open arms at first. I was the team leader. In addition, there was Bill ” Buck ” Nelson, from NASA and Schwickle from McDonnell Douglas. We knew them all from Houston. We rented a two-bedroom apartment overlooking the beach, which we shared with ” Buck ” and Peggy Nelson. Schwickle did not bring his wife and we soon found out why. Every night he picked up a different English girl at the local bars, who was on holiday and was impressed with the American Moon Rocketeer. Schwickle could not give up the temporary pleasures of the flesh. He later divorced and became a Vice President in his company, but to my knowledge never accepted Christ.

In a few days we were ready, but then came “bad news” from Cape Canaveral. They had some problems preparing the vehicle for launch and we would have to stand by. A different one of us went by the tracking station to check the messages, while the rest of us became full-time tourists. The other flight controllers were deployed around the world at Corpus Christi, Texas and the Australian outback. They did not enjoy the delay. The standard joke among us for years afterwards, was that they would call Bermuda and ask, ” Where’s Swalley?” only to be told “He’s at the beach”.

After two weeks of waiting Joanne and Peggy had to see about kids. Buck and I moved into a room together at a local cheaper hotel. One day I was sitting on the front lawn reading when “Buck” came running all excited. He had been fishing off the beach and caught a record-size fish. He had it mounted and sent home. His picture was in the local paper and I guess he still holds that record.

Shortly thereafter the problems were cleared up and July 5th was announced as the launch date. During the wait there had been several other launches, so I called for a simulated mission on July 4th. Boy, was I unpopular! However, after a few minutes into the simulation, it became obvious to everyone that we were nowhere near ready to support the next day’s launch. Without that simulation, it would have been most embarrassing to say the least.

On the morning of the launch, we were to be at the station about 5 or 6 am. We got up and started out in the dark on our motor bikes. Halfway there, I looked over and saw that “Buck” did not have his helmet. You could not get on the Air Base, where the NASA tracking station was located without your helmet. I yelled at him to go back and get his helmet and I would go ahead and order his breakfast and have it waiting for him at the Officer’s Mess. We ate and the three of us started around the end of the runway toward the tracking station with “Buck” in the middle. When we were still about a couple hundred yards from the station, “Buck’s” bike began to sputter. He was running out of gas. I yelled to Schwickle to put one of his feet on the back fender of “Buck’s” bike and I did the same. We pushed him the rest of the way to the station. I jumped off my bike and ran into the station and plugged in my headset in time to hear “Bermuda?” The station guys gave me a thumbs up and I said, “Bermuda is green and ready to support the launch”. Right then I could have cheerfully killed “Buck”.

Part way through the countdown, one of the two TV cameras looking down into the hydrogen tank failed. We had debated such a situation at length and concluded that we had to see and could not lift off with only one camera working. The pressure was on Gordon as Experiment Flight Director. Von Braun came on the line and asked Gordon to call him offline. In a few minutes, Von Braun came back on and said Mr. Platt had explained the importance of the TV, and that he would take full responsibility for launching with only one operating. Fortunately, the one remaining camera worked flawlessly. Had it not, we would have had a hard time reconstructing what went on in that tank with the few liquid-vapor sensors that we had. Not only did the camera work, but also the picture was received a lot longer at the Cape than was expected. So, when I continued to describe what was going inside the tank, they tried to tell me that they could still see too. But I was too excited and never even heard them. I was kidded about that for a long time. But, I never was too good at listening in the headset and carrying on another conversation at the same time.

On the way home after the launch, we read in the paper where the spent stage had blown up in orbit. The Air Force radar tracking guys were most upset, since it meant a lot of pieces to track and interfered with detecting incoming missiles. The blow up was no surprise to us. We had planned to let the pressure in the tank build up and see what the tank’s ultimate failure strength was. It was just a bonus test to us. Unfortunately, no one had thought of the problems it would cause the Air Force and our management had not fully understood what the last pressure differential test was. Poor old Gordon caught a lot of heat for that one too. So, it turned out that being the program manager was not such a hot job as I first thought it was. He was stuck in Houston in the rain, was resented by Houston for even being there- a threat to their cherished role as flight directors- and caught a lot of heat.

After the flight, I wrote a lot of technical papers analyzing the results and was in great demand as a speaker. Looking back, we gave away to the world and in particular the Russians a lot of valuable and expensive information. However, they were never able to get their program off the ground. Their rocket blew up on the pad we later learned, killing a lot of their top engineers. The only classified data in the Apollo program was the detailed engine performance. But knowing the weights and vehicle sizes, you can calculate that reasonably accurately.

During the course of preparing for the flight, I made several trips to Washington with Dr. Von Braun on the NASA plane. One evening we returned home to Redstone Airfield about midnight. NASA taxis were waiting at the airstrip to take us home. Dr. Willie Marazek was the director of the Structures and Propulsion Laboratory and was my boss. Dr. Marazek grabbed his suitcase and my bag and threw it in the trunk of one of the taxis. We lived near each other. As we started to get in the car, the driver said, “I’m sorry this is Dr. Von Braun’s car”. Dr. Von Braun was standing near by and overheard the conversation. He walked over and told the driver ´Take these guys on home”. The poor driver said apologetically “I have been told, that only you can ride in this car” Dr. Von Braun said “It looks like all the rest. What’s the difference?” The driver starting naming the extra luxury features- carpets in the floor, etc. Dr. Von Braun just laughed and said; “You tell your boss that I said its o.k. Go ahead and get these guys on home.”

In later years one of my co- workers, Tom Shaner, was assigned to Dr. Von Braun as his assistant for one year. One year was about all anyone could take, since the job involved being at his side every working minute including traveling with him. The NASA plane was not capable of coast to coast flights. Since most of our contractors were located on the West Coast, Dr Von Braun traveled on commercial airlines a lot. A message would be waiting at the check-in counter. Tom said the changes in scheduling at the last minute were the trying part. They would be scheduled to go one place when a crisis would arise at another and all the travel plans had to be changed. Sometimes the changes came as late as right before they were preparing to board a plane. Whenever the changes hit, Dr. Von Braun didn’t try to get involved in the decision-making. He always had a full brief case with him. He would calmly find a quiet place to work while Tom rearranged things.

Dr. Von Braun was a licensed pilot and he enjoyed flying co-pilot on the NASA plane whenever he could. Our pilot most of the time was George? a retired military pilot. George had flown P-51 propeller fighters and jet fighters. George also had an autographed picture hanging in his den from? whom he had also flown. After I retired from NASA and was serving as the Director of Education at Willowbrook Baptist Church, I participated in my first funeral service. It was for George. He and his wife, Goldie, were members there. When he became ill, I visited him in the hospital, and we talked about airplanes and his flying experiences. He said his closest call to being killed in an airplane was when he was an instructor. A French trainee was practicing landings in the old WWII, dependable Texas Trainer. On a landing approach, the guy didn’t flare out as he approached touchdown and hit the runway so hard that the engine broke free from the front of the plane. The trainee and George were left sitting in the rest of the plane with aviation gas spilled all over and the danger of fire and explosion any second. Goldie said George freed himself and pulled the trainee, who was still frozen to the control stick, from the wreckage. George in his usual modesty left that part out.

Hans Paul

My Division chief was Hans Paul. I understand that in his younger days he had been a real tyrant but by the time I came along he had mellowed and was a fatherly mentor to us young engineers. Mr. Paul was very impressed with American advertising, particularly the concise wording, the impact of the words and, when rightly chosen, their ability to get results. Most briefings then were made using poster size charts mounted on an easel and hand lettered with colored pens. It took a lot of time to make them. Inevitable when we would have a review with Mr. Paul, he would start wordsmithing. If we said—Instead of — would it have a greater impact? We really dreaded all the rework. Many times I felt like yelling out “What about the content? How about the engineering there?” But, of course, I kept my mouth shut and dutifully joined in on improving the effect of the charts.

DR. H. G. L. KRAUSE

Dr. Krause had been a professor in Germany and joined the Von Braun team in the U.S. after NASA was formed. His specialty was predicting the movement of the planets, etc. with extreme accuracy. I got to know him because I needed some data for a computer program I was developing to predict the heat incident on an object orbiting the earth like a fuel tank. He was the typical absent-minded professor. So engrossed in his work that he hardly knew the rest of the world even existed.

I found him sitting in the cafeteria at work one day very despondent. I asked him what the problem was and he just shook his head and said, “I‘ve lost everything. I’ve lost everything I own.” After much questioning, I found out that he had lost his checkbook. “Were the checks signed?” “No, but I’ve lost everything.” It took a lot of effort to convince him that he really hadn’t lost anything after all.

Dr. Krause drove a Volkswagen Beetle, which he was very proud of. But one day he said, “I’m going to trade that damn beetle.” “Why?,” I asked. “Yesterday I was stopped at a traffic light. I looked over and there was a Pontiac beside me. The other driver looked at me and I looked at him. I leaned over the steering wheel and got a firm grip and revved my engine. The other driver accepted the challenge. When, the light turned green. I stomped the gas pedal intending to leave that Pontiac like he was sitting still, but he beat me. I’m going to trade that damn bug.” And he did, for a powerful Pontiac.

As summertime approached, I asked Dr. Krause if he had any vacation plans. He replied that he had rented a cabin for two weeks at nearby Monte Sano State Park. To which I replied, “Well, I know your wife and two children will enjoy that.” “Oh, they are not going. I am going by myself. I need to be alone for two weeks to catch up on my technical reading. I’m behind. I told her when I married her that she would have to make some sacrifices.” I guess it’s all in your point of view. But two weeks away from a sweet young blond wife is not my idea of her sacrificing.

The Internal Revenue audited Dr. Krause, because of the enormous deductions that he had claimed for professional expenses. To justify the expense, he invited them out to his house and showed them his library. When they finally got free several hours later, they were not so sure that he had claimed enough.

WHY SPEND MONEY ON SPACE?

Why spend all this money going to space when there are such pressing needs here on earth? First of all, it inspires the youth of the nation and challenges them to excel in the sciences. I believe that a lot of the technical advances of today got there start in the investment the nation made in putting man on the moon and our economy is fueled by technology. Our studies show that enrollment in engineering and the sciences during and after that period jumped. We are certainly sadly lagging the world in those fields today.

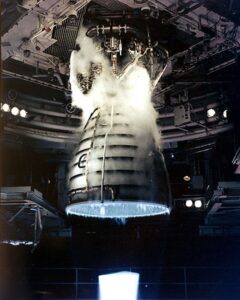

Secondly, there are a lot of technical spin offs. All of the laparoscopic, less invasive, surgery today is made possible by the ability to see around curves using optical fibers. One of the first uses of that technology that I knew of was to look into a rocket engine to inspect the turbine blades for erosion without having to take the engine apart. I don’t know if it was discovered as part of the Apollo program or not, but its development was certainly accelerated by it. There are thousand of other such stories. We used to publish an annual “Spin Off” book until congress prohibited it saying no government agency could promote its own self in that way. In my experience, those spin offs tend to just naturally occur more frequently as you progress toward a defined, specific goal as opposed to saying to a scientist “Here is some money. Go do good research.”

Finally, as Dr. Von Braun used to say “all the money spent on space is after all spent on earth.”

We need something to challenge our youth technologically again. Boys, in particular, don’t think that it is cool to study math and the sciences. I don’t know what it could be unless it’s a manned trip to Mars. A lot of people will argue for unmanned exploration and certainly a lot can and should be done there. However, an inanimate machine isn’t that exciting to a lot of people. The Chinese are now beginning to replicate our nations space accomplishments and are talking of space stations and trips to the moon. However, I think that they will hit the reality that a trip to Mars is so expensive that it will have to have international cooperation. Maybe that is our next major challenge, but it is off in the future.

Until then, maybe we set a goal of Once Around for Everyone Earth Bound. The Trip of a Lifetime. This time spend the money to get the cost of going to low earth orbit down to where everyone could afford one trip. You might even get the private sector involved by offering a $100M prize.

As we worked on placing a man on the moon and returning him, the thought that it couldn’t be done never entered my mind. Nor did I ever hear anyone else say “This is crazy, we can’t do it.” The focus was on how to do it. We were nearly all young and led by the brilliant German rocket scientists – especially Dr. Von Braun. Dangerous? Yes! Impossible? No! There were some speculations by astronomical geologists that the moon’s surface was covered with a thick layer of fine powder. When the space craft landed, it would just sink to the bottom and disappear. But there were others who thought that the powder wasn’t that thick. The latter groups were proven right. You can get a feel for the thickness by looking at the pictures of the astronauts’ footprints on the lunar surface. And there was concern that if you landed on the edge of a crater or a boulder, you might tip over but no one on the team was questioning our ability to succeed.