by Willie Weaver

This is an account of just one of the many times where NASA helped push our electronic world out of the old technology and into the transistor/solid-state electronic era. I have wanted to tell this story for some time, but have just recently taken the time to write it down.

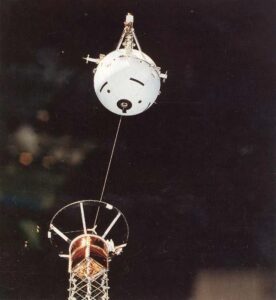

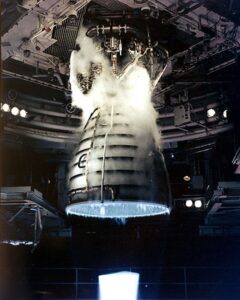

The development of the SATURN system of launch vehicles proceeded from the Saturn 1 – Block 1 to the Saturn 1 – Block 2, and then to Saturn 1B -Block 1, and Saturn 1B – Block 2, and then on to the Saturn 5. We began to expand and upgrade our ground test equipment as new technology and schedule considerations presented the opportunities. In our telemetry ground stations, we discarded the oscillograph recorders, whose long scrolls of data had to go through a photographic development and drying process, and installed recorders that used thermal sensitive paper that came out of the machines fully developed.

We had performed the Redstone and Jupiter telemetry testing with ground stations whose electronics were almost entirely based on vacuum tube technology. During Mercury/Redstone testing we acquired some equipment that used the new transistor technology in special circuits. The flight equipment of the Saturn rocket would make more use of transistor circuits.

Our first real leap into the world of transistors was when we added a new set of signal discriminators in preparation for Saturn tests. Many of our engineers and technicians had little knowledge or experience with transistor circuits. Luckily, we had Tom Flanders on our contractor support staff. Tom had taught transistor circuits at Georgia Tech while getting his masters degree in electronics. He left the academic world and hired on with our NASA contractor, Chrysler Corporation. We got approval, through the MSFC training department, for him to teach Transistor Circuits to all those in the laboratory who desired such training. That worked out well for NASA and for those who took the training.

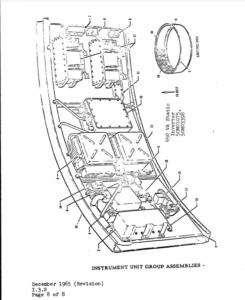

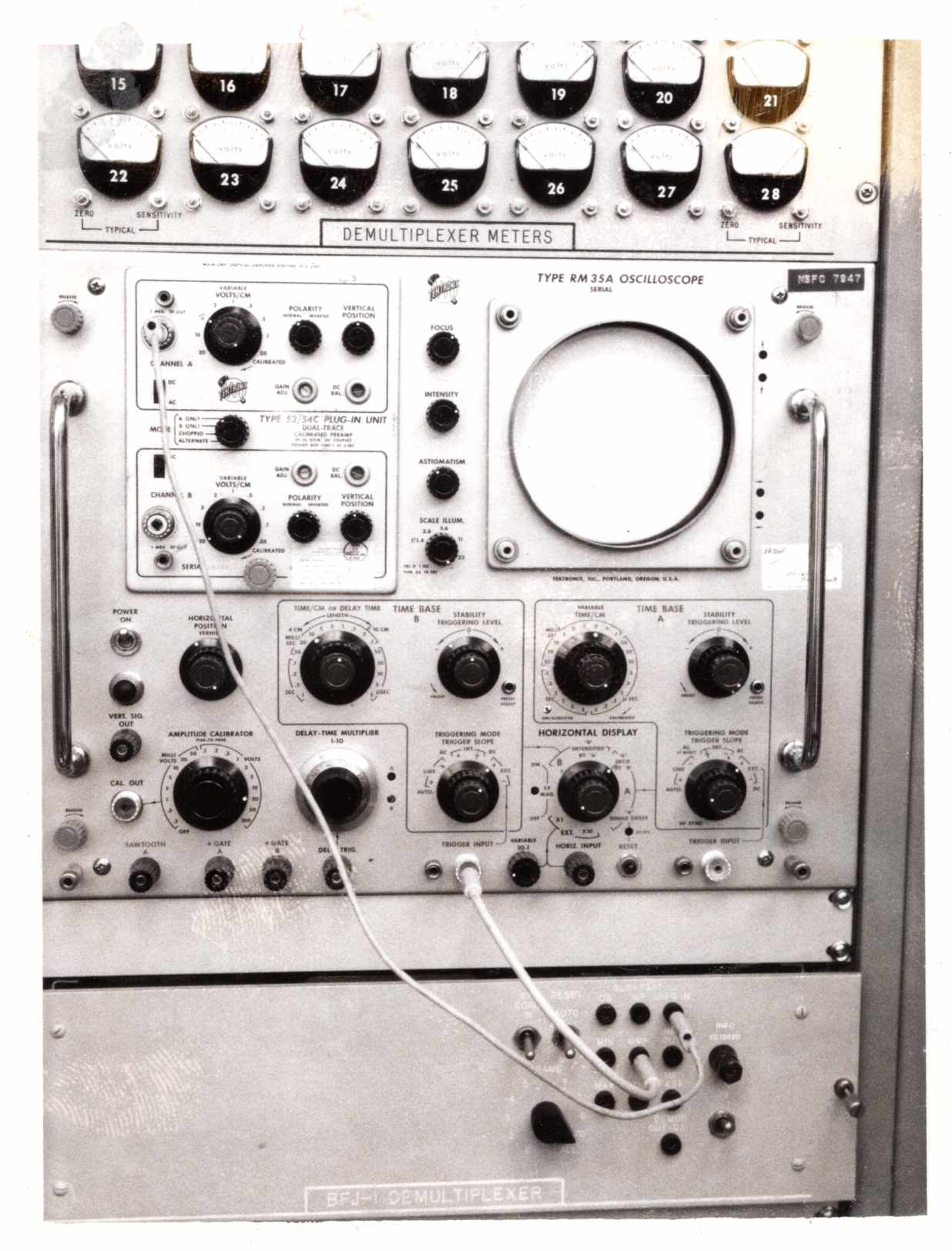

The Saturn 1st stage data system had flight multiplexes that placed the output of 300 sensors into a data stream and sent it to a ground station where a demultiplexer would separate the 300 signals. Our existing demultiplexer could process the 300 signal data stream, but it suffered from over heating and vacuum tube failures. Also, during operation it required constant adjustments. We were in dire need of a replacement before we began the Saturn 1B and Saturn V tests. We had talked with several vendors in the telemetry market about the possibility of a demultiplexer based on transistor technology but none of them offered such an unit . One vendor did offer to supply a transistor based demultiplexer on a cost-plus development contract.

Tom Flanders had been working with the technician who was responsible for the demultiplexer in an effort to solve some of its problems. He told me that rather than waste his time on the old machine I should let him just build a new machine. He assured me that he could do that with transistor logic boards and other components currently available on the market. I asked him and my lead telemetry technician, Prince Jones, to explore his idea further and if it still seemed feasible, to bring me a proposal which we could take to our Advanced Projects office for possible funding.

When they had the proposal ready, we presented it to Paul Davis, the Laboratory lead for Advanced Projects. This was the same Paul Davis that I had worked for in the Measurement Test Section during my first Coop session. He gave us approval to proceed and made funds available for the equipment and parts we needed.

I assigned another contractor engineer, Earl Benson, to work with them. The designation for the effort and eventually the final Design became “BFJ” after the thee men working on the project. Along the way some doubters begin to say BFJ stood for “Big Fat Joke”. However, in a few weeks, they produced a breadboard version that met the basic requirements. Along the way, Earl Benson left the project and Charles Mandy took his place, but the BFJ name stuck.

Several more weeks to work out the component layout and design the control panel and, we had a working unit that fit neatly in three drawers of a standard equipment rack and needed only moderate cooling. Whereas, the old model occupied 3 standard racks and required massive cooling. We worked with the designers of the flight multiplexer in a series of verification tests to prove we had a design that could reliably process the output of the flight multiplexer.

We then contracted with Brown Engineering to build units for our Systems Test telemetry ground station. We also made copies of the design documentation available to other NASA groups and to any vendor that may want to supply similar units for the program.