By Jim Miller

[This adapted excerpt is from the NASA chapter of Jim’s published book Memories of Jim Miller written for his family and friends.]

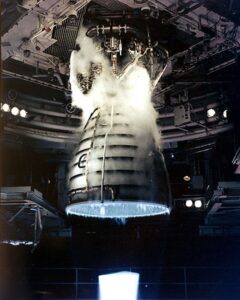

When I arrived at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1963, the center was beginning development of the Saturn family of launch vehicles. I became involved with Marshall requirements for launches at Cape Canaveral and wound up sitting in the blockhouse at the Cape, participating in the electrical system that flew on the Saturns.

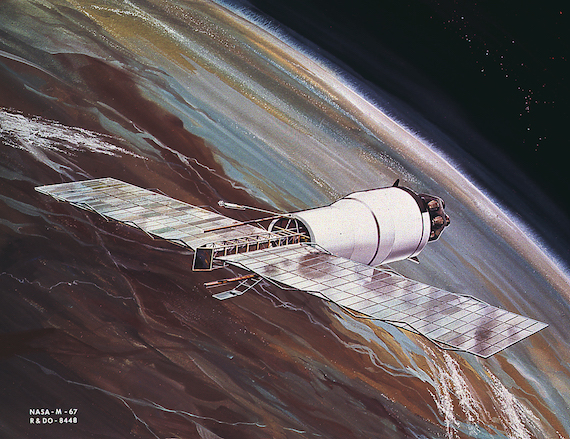

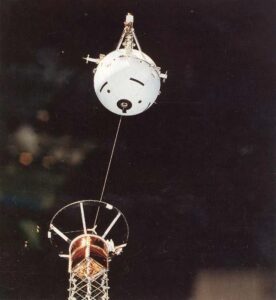

The first satellite system that I had responsibility in was called Pegasus. We ended up flying three of these satellites on early Saturns. I, with a small team of four other engineers, was assigned to assist in the development of the electrical systems for Pegasus, which was a satellite designed to test the structural integrity of the systems for the Apollo program. The Pegasus flew very long panels of sensors, designed to measure the meteoroid penetrability of various material thicknesses. This was necessary to determine how thick the skin of the Apollo living quarters needed to be to withstand the meteoroid impacts between Earth and the Moon. In this capacity I ended up traveling often to Bladensburg, Maryland, where Pegasus was being built by Fairchild. Since neither they, nor we, had done this type of thing before, we wound up arguing about almost everything we did, mainly about how the system was laid out for wiring. As far as we were concerned, these were make or break features.

However, the major argument at the time was that the folks in the MSFC Propulsion & Vehicle Engineering Lab (P&VE) thought that, structurally, Pegasus would not withstand the launch vibration and, therefore, would break apart during launch. Thus, our Pegasus team had to contend with that argument, as well. Our small MSFC team supporting Fairchild in the design of Pegasus agreed that we didn’t like the way the design was going and, therefore, determined that we should make Dr. von Braun aware of all of these concerns.

So, we met with Dr. von Braun and reported that we were fearful that the Pegasus would come apart during launch. Our proposal was that we get the Saturn folks to design a net to fly under the Pegasus to catch the pieces when it came apart. (This is not a joke. We actually reported to Dr. Wernher von Braun that we seriously thought the Pegasus satellite would destroy the Saturn launch vehicle.) Dr. von Braun listened patiently to our concerns and then assigned Dr. Eberhard Rees (his Deputy) to travel with our team to Bladensburg and have a design review with Fairchild.

I had the pleasure of sitting with Dr. Rees on the airplane on the way to Bladensburg and he told me that I should not worry about the design, because all projects go through a period in which the engineers would think the worst about the situation. He encouraged me that everything would probably work out okay. Needless to say, we did not fly a net to catch the parts of Pegasus if it came apart. Dr. Rees was right, and everything did work out okay; we flew three vehicles, and they all worked fine.

I did get involved in a later problem, however, which could have been critical. At that particular time we had no indoor facilities at the Cape, such as the Vertical Assembly Building (VAB), to shield a spacecraft (like Pegasus) from something like rain. So, it just so happened that while they were loading Pegasus onto the Saturn, there was a little rain shower that came along and wet everything down.

It was my task, along with my Fairchild technician, to climb up into the payload stage of the Saturn while it was on the launch pad to check for any rain damage. Access to the Pegasus required riding the gantry elevator up to the Saturn payload level (about 250 feet in the air) and then walking across the catwalk. Sure enough, we found that there were three pockets of water captured between the thermal insulation blankets wrapped around the Pegasus. I held a cup while my Fairchild technician took a screwdriver and punched a hole in each of the pockets of water. I captured the water in the cup to carry back for my boss to see.

When I showed the rainwater to my boss, it triggered a rather hefty debate regarding what we should do about the water. The decision was that it would be too expensive to unstack the Pegasus, and there wasn’t really time in the schedule. So, my Fairchild technician and I had to do the best job we could blow-drying the Pegasus that was on the launch pad, and we flew.

That flight went well, as did two additional flights. We were told that the three Pegasus spacecraft provided all the data needed for the proper design of the Apollo spacecraft. In all, I sat through the blockhouse at Cape Canaveral several times during countdown and launch of several of the early Saturn vehicles. I wondered if the blockhouse would actually protect us from an explosion, because we were pretty close; but, fortunately, blockhouses were not used beyond that series of Pegasus-type launches.